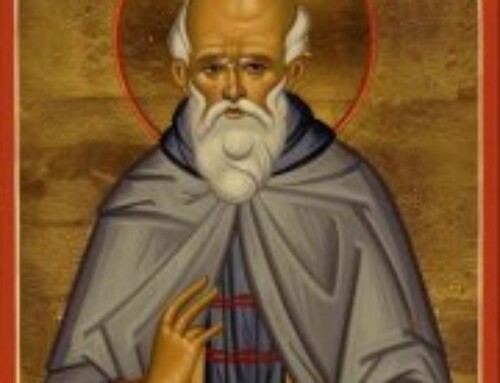

St. Gregory The Theologian (329-389)

In Defense Of His Flight to Pontus De Fuga The Second Oration

Introduction

In 325 AD, the year of the First Ecumenical Council, a Christian woman in Cappadocia managed to convert her husband to the Orthodox Christian faith. Her name was Nonna. Her husband’s name was Gregory. Gregory had belonged to an obscure sect called the Hypsistarians. Nonna and Gregory were people of wealth and position, a patrician couple living in Arianzum in South West Cappadocia.

Within four years of his conversion, Gregory would be a bishop. He and Nonna became the parents of three children: a daughter called Gorgonia, a son also named Gregory, and a second son named Caesarius. Although all three children will lead noteworthy lives, it is Gregory that is of special interest to us. This Gregory, and there a deluge of Gregory’s in the history of the Church, is known to us as Gregory the Theologian. This Gregory, the friend of St. Basil, is champion of Nicean Orthodoxy, Patriarch of Constantinople, leader at the II Ecumenical Council.

He is the author of one of the most important writings on the pastoral life in the early centuries of the Church. Although, ironically, it is an apology for running away from pastoral responsibility, it is one of the most important writings on pastoral life having influenced both St. John Chrysostom and Pope Gregory of Rome.

This important document, called the Second Oration, or In Defense of His Flight To Pontus (sometimes known by its Latin title De Fuga) was written by a man who was only 31 or 32 years of age. (Although he did revise it later in life.) He wrote the document within the first months of being ordained a priest. He was hardly a veteran of pastoral life. Before we examine his famous work, I think we should consider for a moment the times and the man.

The Times

Every century is important in Church History, but the fourth century is clearly historic. The century began with the persecution of the church by the Roman Empire. This, of course, changed with the famous Battle of Milvian Bridge on October 28 in 312 AD., and the accession and conversion of Constantine. The fourth century saw the founding of New Rome, the city of Constantine, in 330. It was the century of Arianism; a struggle in which not only Christian intellectuals took part, but everybody up to and including the Emperors. It was a century of theological debate over the identity of Christ and the meaning of the Trinity. It was the century of Athanasius who managed to be exiled from his church some five times. It was the century of two ecumenical councils. It saw the rise of monasticism in the Eastern Church. It saw the birth of great Christian saints: Gregory the Theologian, Basil the Great, John Chrysostom in the East and Augustine in the West. This was the century of Gregory the Theologian, who lived from 329 to 389AD.

The Life of Gregory

Gregory was born to wealth and position. And according to John McGuckin, this was something that Gregory never forgot. Gregory was a patrician. The family was rich. John McGuckin calls him “an aristocrat to his fingers.” (p. 3)

Gregory’s father is known as “Gregory the Elder”. Imagine for a moment what it would have been like to grow up in a situation where your pastor, your employer, your landlord, and your bishop were all one person—namely your father. Such was life was for Gregory. His patrician father not only was the local landlord, he also built the church for the people of the area, was their pastor and their bishop. McGuckin calls the elder Gregory not a hierarch, but a squirearch”.

I don’t know how seriously we should take him, but McGuckin says that we should not forget that Gregory the Theologian, who has much to say about the theology of the life of the Trinity, and the relationship between the Father and the Son, was a man very concerned with the relationship between himself and his own father….the Son is equal to the Father although He is begotten of the Father….He was forcibly ordained to the priesthood by his father. If PK’s have problem, Gregory (actually a “BK”) had plenty.

Gregory’s mother was Nonna. She was born of a long standing Christian family. The marriage between Nonna and Gregory seems to have gotten the elder Gregory into trouble with his family for having married a Christian. Their son Gregory was very strongly attached to his mother. (As was John Chrysostom) He claims to have been her favorite. Her very “darling” to use his own words.

Gregory’s early education was under a tutor named Carterios. As a young teenager he went to the regional capitol of Caesarea studying grammar and rhetoric. It was there that he probably came to know a man would play a very important role in his life, Basil of Caesarea.

Gregory and Basil shared many things in common. They were both Christians. They were both wealthy aristocrats. They were both brilliant people. Both would be highly educated. Both would be drawn toward the celibate life and to monasticism (although in different ways).

Both had very influential Christian women in their families. Gregory had his mother. Basil’s family seems to have been dominated by his sister Macrina. From Caesarea in Asia Minor, Gregory, his brother Caesarius and their tutor traveled south to the Palestinian Caesarea, which had become famous a center of Christian learning, (I believe where Origin got into trouble) and then on to Alexandria where his brother studied medicine. In 348 at about the age of 18 Gregory left Alexandria sailed for Athens. (He was on his way to Harvard). En route to Athens, Gregory’s ship encounters a fierce storm on the sea which terrifies him.

At Athens Gregory is soon joined by Basil. They live among the aristocrats of the Empire. The future Emperor Julian is among the students. Here at the university they study Rhetoric and Philosophy, the standard education of the aristocracy. These subjects would prepare them for a career in law or civil administration or management of their property or even as a professor. It was the best education that the ancient world could offer. Gregory studied at Athens from 348 to 358 which would have been about ten years. By any standards that is a long time to spend in study.

See page 82 (Gregory), according to McGuckin, “had studied at one of the greatest schools of antiquity for almost ten years. He had absorbed the whole gamut of literature, philosophy, ethics, and the liberal sciences. It had been brought home to him just how eclectic this intellectual world of Late Antiquity really was. In the domain of religion, to which he felt especially drawn, he saw at every turn the conflicting claims of religious systems that thrived on eclecticism, were ready to immerse themselves in an all-embracing universalism, and yet also claimed a distinctive voice within the choir of sirens that sang about human enlightenment and spiritual wisdom. This experience was within Gregory like a great sea, teeming with life beneath its surface. It was of inestimable importance for him as a Christian intellectual of the fourth century, for the fertile ambivalence of the Hellenistic myths of religious and philosophical truth made him face up to the massive problem facing his own religion in its claim for particularity alongside universality. Its specifically historical rootedness in the life and death of Jesus, sat ill at ease with its claims to be a universally relevant Logos-religion of the highest intellectual standing. Its claims for absolute allegiance jarred with the vague and open-ended spirit of the age, where religions were mixed and assorted, like personal adornments, to fashion a style.”

The first to leave Athens was Basil. Basil visited the monasteries of Egypt and then went home to establish his monastery at Annesoi. Gregory left soon afterward. It may have been that Basil hoped Gregory would join him, but the two seem to have irreconcilable views on monasticism. Basil wanted the more rigorous coenobitical life as lived in Egypt. Gregory wanted the life of the hermit scholar. “He wanted to combine a gentlemanly solitude, in which he could study and

contemplate, with a ready access to civilized society as befitted his rank”. (p. 87) Both his family and the monks who lived in the vicinity of Nazianzus would have looked a this kind of monasticism as something eccentric. (p. 87) (Jesuits?)

In 359, after he left Athens, traveling leisurely he stopped to visit the new capitol Constantinople and after journeying though Asia Minor, he arrived in Nazianzus. Gregory went into a semi-seclusion on the family estate. He made several visits to Basil at Caesarea over the next two years. It was obvious that he and Basil had differing ideas about monasticism. (In 356, while Gregory was still in Athens, Eustathios of Sebaste had taken Basil on a tour of the monastic sites of Egypt, Palestine and Syria.) McGuckin says that Basil was, in effect, an authority on monasticism.) Because of Basil’s domineering attitude Gregory could not join Basil at Annesoi.

Gregory was certainly attracted to solitude. “However much I wanted to be involved with people I was seized by a still greater longing for the monastic life, which in my opinion was a question of interior dispositions, not of physical situation. For the sanctuary, I had reverence….but from a distance.” (p. 89)

Gregory no doubt was trying to resolve his vocation. Should he be a solitary ascetic? Should he serve the church as a priest or a bishop? The pastoral life would involve working among people; the monastic life would mean separation from people. Could he live both lives? Was his bishop father putting the pressure on him to do something with his education and his life?

P. 96-97 Somewhat in the spirit of Origen, Gregory pursued the intellectual path to God. He preferred to transform culture rather than reject it. Gregory lived this solitary intellectual life on the family estate from 359-361. It seems that Gregory’s father wanted him to take over management of the estate. Gregory insisted that his interest in religious matters prevented this. (Can’t you just hear the conversations between Gregory the Elder and his wife Nonna?) Things came to a head in the celebration of Christmas in the year 361 when Gregory was forcibly ordained by his father. The Christian Emperor Constantius had died that year and was replaced

by Julian the Apostate who wanted to destroy Christianity. Tough times were coming. Gregory had used the excuse of his call to religion to refuse to manage the family estates. His father had called his bluff. If religion were to be his life, it would be as a priest.

Without even preaching his first sermon Gregory runs away. Predictably he runs to Basil. But now that he is a priest Basil does not encourage Gregory to take up a permanent residence in his monastic setting. Gregory now owed obedience to his bishop. They spend several months together working on Origen after which Basil encourages Gregory to go home. How could he return with some dignity? Fate seems to have come to his rescue. His father had signed a less than orthodox statement about Christ. He was needed as a theologian and orator to bail out his father.

Upon his arrival back in Nazianzus Gregory writes this Second Oration, his defense for his flight, which turns out to be one of the most important writings on the pastoral life from the patristic era. McGuckin tells us that this Second Oration “was to be extensively remodeled and amplified by Gregory in the aftermath of his retreat from Constantinople in 382, and therefore needs to be read with some caution….”(p. 106)

COMMENTARY ON THE SECOND ORATION

#1

Having subjected himself to the Lord, Gregory begins the Oration by addressing the question of his flight after the ordination. He acknowledges that among the community at Nazianzen there are those who are against him and those who are for him. He knows that people like nothing better than to talk about other peoples business. He is going to set the record straight. As we will see, Gregory gives four specific reasons for his flight.

#3

What he has done is neither out of ignorance nor out of contempt for divine law. There are, in the church, those who rule and those who are ruled.

“God has ordained,” he says, “ that those, for whom such treatment is beneficial, they should be subject to pastoral care and rule, and be guided, by word and deed in the path of duty; while others should be pastors and teachers, for the perfecting of the church, those, I mean, who surpass the majority in virtue and nearness to God, performing the functions of the soul in the body, and of the intellect in the soul; in order that both may be so united and compacted together, that, although one is lacking and the other is pre-eminent, they may, like members of our bodies, be so combined and knit together by the harmony of the Spirit, as to form one perfect body, really worthy of Christ Himself, our Head.”

The structure of the church, in which some are pastors and others are guided by pastors has been ordained by God. But pastors, he insists, must be chosen from those who surpass the majority in virtue.

#4

Without structure anarchy would reign. It would be wrong and disorderly if everyone would want to be a ruler in the church; but it would be also wrong if no one would accept the pastoral office “whether it be called a ministry or a leadership…” “And by whom would God be worshipped among us in those mystic and elevating rites which are our greatest and most precious privilege, if there were neither king, nor governor, nor priesthood, nor sacrifice….” Here is recognizes the liturgical role of the pastor. (king? governor?)

#5

Aside from their spiritual qualities who should be chosen for the pastor office? It is not “inconsistent that those who are devoted to the study of divine things, to ascend to rule from being ruled….”Gregory gives several examples of men rising from the ranks. He notes that he was not ashamed of the rank that he was elevated to….desiring a greater rank. He was ordained a priest and not a bishop. Gregory would argue elsewhere that the pastoral life is charismatic, but here he acknowledges the importance of the study of sacred things. The priest must be educated.

#6

In Paragraph six, Gregory returns to the issue of why he ran away. “What were my feelings and what was the reason for my disobedience?” I know that I was not acting like my usual self “And the causes of this you have been long waiting to hear.” The first reason was as he says, he was astounded at the unexpectedness of what happened. “And losing control of my reasoning faculties…, and my self respect gave way.” (He freaked out)

“There came over me”, he says, “an eager longing for the blessings of calm and retirement of which I had from the first been enamored to a higher degree, I imagine than any other student of letters….I could not submit to be thrust into the midst of a life of turmoil by an arbitrary act of oppression and to be torn away by force from the holy sanctuary of such a life as this.” (7) “For nothing seemed to me so desirable as to close the doors of my senses, and, escaping from the flesh and the world, collected within myself, having no further connection than was absolutely necessary with human affairs, and speaking to myself and to God, to live superior to visible things, ever preserving in myself the divine impressions pure and unmixed with the erring tokens of this lower world, and both being, and constantly growing more and more to be a real unspotted mirror of God and divine things, as light is added to light, and what was still dark grew clearer, enjoying already by hope the blessings of the world to come, roaming about with the angels….” “If any of you has been possessed by this longing, he knows what I mean and will sympathize with my feelings at that time.”

Gregory wanted to be a contemplative. The pastoral life threatened any chance of living this life.

#8

But there was something else, his third reason. This feeling may be base or noble, he is not sure, but he will reveal it. The reason he ran from the priestly life was that he is very unedified with many of those who sought to become priests. (If we think that the Fathers lived in a time when the churches were all led by saints, this would suggest otherwise.)

“I was ashamed of all those others, who, without being better than ordinary people, nay, it is a great thing if they not be worse, with unwashen hands, as the saying runs, and uninitiated souls, intrude into the most sacred offices; and before becoming worthy to approach the temples, they lay claim to the sanctuary, and they push and thrust around the holy table, as if they thought this order to be a means of livelihood, instead of a pattern of virtue, or an absolute authority, instead of a ministry of which we must give an account. In fact they are almost more in number than those whom they govern.” “…. For at no time, either now or in former days….has there ever been such an abundance as now exists among Christians, of disgrace and abuses of this kind.”

Gregory not only wanted to be a contemplative. Gregory was also embarrassed at the unworthy and unedifying people who were already serving the church. He now comes to the fourth reason for his flight.

#9

“I did not, nor do I now, think myself qualified to rule a flock or herd, or to have authority over the souls of men.” Taking care of sheep is one thing; all you have to do is feed them. But people are something else, you have to be concerned with their virtues. And you have to place them ahead of yourself.

#10

There is also the question of authority. “Hard as it is for (a person) to learn how to submit to rule, it seems far harder to know how to rule over men, and hardest of all, with this rule of ours, which leads them by the divine law and to God, for its risk is… in proportion to its height and dignity.” The pastor must be a teacher of morality. He must teach them the divine law and this is a very difficult task.

#11

Unfortunately if a pastor has vices, these vices will have a much quicker impact on his subject than will his virtues. “Wickedness….. has the advantage over goodness and most distressing it is to me to perceive it, that vice is something attractive and ready at hand, and… nothing is so easy as to become evil… while the attainment of virtue is rare and difficult.”

#12

Man seems to be predisposed toward evil.

#13

The pastor must first of all avoid giving a bad example—-that “we undertake to heal others while we are full of sores.”

#14

Moreover, it is not enough that the pastor keeps himself free from sin. This alone is not enough for the man who would instruct others in virtue. “For the one who has received this charge not only needs to be free from evil, for evil is, in the eyes of those under his care, most disgraceful, but also to be eminent in good…And he must not only wipe out the traces of evil from his soul, but also inscribe better ones, so as to outstrip men further in virtue than he is superior to them in dignity. He should know no limits in goodness or spiritual progress.” The pastor should not measure his success by comparing himself to other people; he should measure himself by God’s commandments.

#15

In his dealings with people, the pastor must remember people are different from one another. Evil or base conduct is deserving of condemnation in a private person. But failure to attain virtue in a leader is a serious matter. It is better to rule by persuasion rather than by force. “That which is the result of choice is both most legitimate and enduring, for it is preserved by the bond of good will.” We should “tend the flock not by constraint but willingly”. (Gregory’s advice still holds true. You cannot force people to be good.)

#16

But in case a man might think that he is good enough to hold a pastoral office, Gregory states:

“But granted that a man is free from vice, and has reached the greatest heights of virtue: I do not see what knowledge or power would justify him in venturing upon this office. For the guiding of man, the most variable and manifold of creatures, seems to me in very deed to be the art of arts and science of sciences. Anyone may recognize this, by comparing the work of the physician of souls with the treatment of the body; and noticing that, laborious as the latter is, our is more laborious, and of more consequence from the nature of the subject matter, the power of its science, and the object of its exercise. The one labors about bodies, and perishable failing matter, which absolutely must be dissolved and undergo it fate….”

#17

“The other is concerned with the soul which comes from God….”

(Here I believe we have one of Gregory’s most important comparisons, that between the physician and the pastor.)

#18

He reminds his hearers of the difficulty that the human physician has in diagnosing and curing a physical illness. “Place and time and age and season and the like are the subjects of a physician’s scrutiny; he will prescribe medicines and diet, and guard against things injurious, that the desires of the sick may not be a hindrance to his art. Sometimes, and in certain cases, he will make use of the cautery or the knife or the severer remedies; but none of these, laborious and hard as they may seem, is so difficult as the diagnosis and cure of our habits, passions, lives, wills, and whatever else is within us, by banishing from our compound nature everything brutal and fierce, and introducing and establishing in their stead what is gentle and dear to God, and arbitrating fairly between soul and body; not allowing the superior to be overpowered by the inferior, which would be the greatest injustice; but subjecting to the ruling and leading power that which naturally takes the second place: as indeed the divine law enjoins….”

And while people are usually cooperative with their doctors, it is quite another matter with their spiritual physician. Very often the people we want to help are in what Gregory calls “armed resistance” against the one who is trying to help them.

#20

If someone tries to help us spiritually, we are inclined to hide our sins. Thinking that if we avoid the notice of men, we can avoid the notice of God. Or, we try to make excuses for our sins, closing our ears refusing to hear the voice of the one trying to help us. Or worse yet, people can sometimes brazenly go on sinning.

#21

The human physician deals with things on the surface or what is not too deep in the human person. The spiritual physician on the other hand is dealing with things, whose causes are deeply hidden, in what Gregory calls the “hidden man of the heart”. And we have another adversary who is out to destroy the patient, Satan.

In this struggle the pastor must have “faith, and of still greater cooperation on the part of God, and as I am persuaded, of no slight counter maneuvering on our part.” The pastor must be a person who has very strong faith, is blessed by divine grace, and who is ready for a fight.

And what is the purpose of this struggle?

“the scope of our art is to provide the soul with wings, to rescue it from the world and give it to God, and to watch over that which is in His image, if it abides, to take it by the hand, if it is in danger, or restore it, if ruined, to make Christ to dwell in the heart by the Spirit: and, in short, to deify, and bestow heavenly bliss upon, one who belongs to the heavenly host.”

The whole plan of salvation was for this— to restore us to God. The pastor works within the context of the paschal mystery; the life, suffering, death and resurrection of Christ which he says is a “training for us and at the same time our healing, restoring the Old Adam to the place where he fell, conducting us to the tree of life…”

(#23-24-25)

#26

“Of this healing we, who are set over others, are the ministers and fellow-laborers; for whom it is a great thing to recognize and heal their own passions and sicknesses.”

#27

The human physician labors and suffers to extend the life of someone who may not even be a good person. But whether the patient is good or bad, he is not going stay on this earth forever.

#28

And if the human physician labors hard, how much harder should we work for a being that is blessed with immortality and who is destined for either eternal punishment or eternal praise.

Now to the treatment of the patient. Gregory insists that you have to carefully discern between people. Different people require different strategies. There is a difference between men and women, young or old, the cheerful and the depressed, the sick and the not. The married and the unmarried differ as do the hermits and the cenobites, the rustics and the rich and so forth. The point being that there is no one way of treating everyone. (Pope Gregory will take up this theme in very specific terms.)

#30

The same remedy is not useful for everyone. As the doctor does not give the same medicine to all, neither can the pastor. Some people will be led by your teaching. Other people will be led by your example. Some, he says need the spur (a kick in the pants?), others have to be curbed in their behavior; some have to be roused up and smitten with the word.

#31

Some people benefit by praise, others by blame. Some you can encourage and some you must rebuke. Some you can speak to publicly and some only in private.

#32

Some people are puffed up with their own wisdom. Some you must pretend not to see lest they be driven to despair. Sometimes you have to seem to be angry with people without actually being angry.

#33

Gregory admits that this discernment is a very complicated matter and “to give you a perfectly exact view of them, so that you may in brief comprehend the medical art is quite impossible….” It will be a matter of experience and practice.

#34

It is a matter of walking on a tight rope. You have to keep your balance. You are walking on the Kings Highway.

#35

Gregory now comes to what he says should be the first of the pastoral duties, which is the ministry of the word.

“In regard to the distribution of the word, to mention last the first of our duties, of that divine and exalted word, which everyone now is ready to discourse upon; if anyone else boldly undertakes it and supposes it within the power of every man’s intellect, I am amazed at his intelligence, not to say his folly. To me indeed it seems no slight task, and one requiring no little spiritual power, to give in due season to each his portion of the word, to regulate with judgment the truth of our opinions, which are concerned with such subjects as the world or worlds, matter, soul, mind, intelligent nature, better or worse, providence which holds together and guides the universe….”

# 36

They are concerned with our original constitution, and final restoration, the types of truth, the covenants, the first and second coming of Christ. His Incarnation, sufferings and dissolution, with the resurrection, the last day, the judgment and recompense, whether sad or glorious; to crown all with what we are to think of the original blessed Trinity. Now this involves a very great risk to those who are charged with the illumination of others.

In other words, know your theology. At this point Gregory points out the problems of Arianism and Sabellianism and the issue of the Trinity which plagued his century.

#39

He tells us that he brings these matters up only to show how profoundly difficult it is to speak about them. It is very difficult to speak of them in front of a large gathering of people. You are almost certainly going to be misunderstood.

#40

There will always be people who are completely unwilling to give up their private opinions and the “accustomed doctrines in which they have been educated.”

#42

Especially problematic are those people who “listen to all kinds of doctrines and teachers, with the intention of selecting from all what is best and safe, in reliance upon no better judges of the truth than themselves.” (nothing has changed.) (“I will find a church to suit my needs”.) In the end these people will often become disgusted with all the various doctrines and give up entirely.

#43

Better he says to teach people the truth when they are young. “To impress the truth upon a soul when it is fresh, like wax not yet subjected to the seal, is an easier task than inscribing pious doctrines on the top of inscriptions–I mean wrong doctrines—.”

#44

Gregory reinforces his basic approach to pastoral method.

“Since the common body of the church is composed of many different characters and minds…it is absolutely necessary that its ruler should be at once simple in his uprightness in all respects, and as far as possible manifold and varied in his treatment of individuals, and in dealing with all in an appropriate and suitable manner..

#46

Don’t adulterate the word of God, talking like a ventriloquist and a chatterer. Have the humility to listen to those who are more experienced. It would be difficult to understate the importance of both spiritual and intellectual preparation for the man who wishes to be a priest or bishop.

#47-49

To undertake the training of others before being sufficiently trained oneself is the height of folly. People want to be spiritual authorities while they are still spiritual children. They learn two or three expressions of pious authors which they have actually not read themselves or learned, but only by hearsay and take the chair of teaching like a philosopher. “We ordain ourselves men of heaven and seek to be called Rabbi.” We talk about our dreams which are nothing other than drivel.

The point of all this is that people have to be trained and experienced as teachers of God’s word.

#50

No one would get up and play a flute or dance before others without being taught how to do so. The same person will get up and spout wisdom without having been taught anything. It is very dangerous he says to put a man teaching others who is not aware of how ignorant he is. All this is vain glory.

Things are so problematic it would take a Peter or Paul to straighten things out. And with name of Paul, Gregory finds a wonderful model for the pastoral life.

#52

All the other scriptural models, Gregory will now “pass by, to set forth Paul as the witness of my assertions, and for us to consider by his example how important a matter is the care of souls, and whether it requires slight attention and little judgment. He then summarizes all the sufferings that Paul endured in his life as an Apostle.

#54

What of the laboriousness of his teaching? The manifold character of his ministry? His loving kindness? And on the other hand his strictness? And the combination and blending of the two; in such wise that his gentleness should not enervate, nor his severity exasperate? He gives laws for slaves and masters, rulers and ruled, husband and wives, parents and children, marriage and celibacy, self-discipline and indulgence, wisdom and ignorance, circumcision and uncircumcision, Christ and the world, the flesh and the spirit. On behalf of some he gives thanks, others he upbraids. Some he names his joy and crown, others he charges with folly. Some who hold a straight course he accompanies, sharing in their zeal; others he checks, who are going wrong. At one time he excommunicates, at another he confirms his love; at one time he grieves, an another he rejoices; at one time he feeds with milk, at another he handles mysteries; at one time he condescends, at another he raises to his own level; at one time he threatens with a rod, at another he offers the spirit of meekness; at one time he is haughty toward the lofty, at another lowly toward the lowly. Now as least of the apostles, now he offers a proof of Christ speaking in him; now he longs for departure and is being poured for as a libation, now he thinks it more necessary for their sakes to abide in the flesh. For he seeks not his own interest, but those of his children, whom he has begotten in Christ by the gospel. This is the aim of all his spiritual authority, in everything to neglect his own in comparison with advantage of others.”

The pastoral office is not to be taken lightly. Lest we think otherwise, Gregory reviews the Old Testament prophets and what they had to say about the priests and shepherds of Israel, not so much as models of pastoral life, but as those who warned the priests of the Old Law.

# 57

Hosea inspires me with serious alarm. He warns us that to the priests and leaders will come judgment.

# 58

The prophet Micah accuses the priests for teaching for hire and the prophets divine for money. The result of this was the downfall of Jerusalem.

#59

The prophet Joel summons us to wailing. The priests should haunt the temple in sackcloth and ashes because there was no fitting sacrifice.

#60

The Prophet Habakkuk upbraids the leaders and teachers of wickedness. He cries out to God because of the injustice of the religious leaders.

#61

Malachi brings bitter charges against the priests, reproaching them for offering polluted sacrifices on the altar.

# 62

Zachariah testified against the priests.

#63

Should we not tremble at the charges and the reproaches against the shepherds?

#65

And what of Ezekiel’s condemnation of the shepherds. “Her priests have violated my law and profaned my holy things”. “My flock became a prey, behold I am against the shepherds, and I will require my flock at their hands.”

#67-68

Finally, Jeremiah who prophesied “Many pastors have destroyed my vineyard and have polluted my portion. Woe be to those pastors that destroy and scatter the sheep of my pasture.”

#69

Gregory now turns to the teaching of the New Testament

“Why need I speak of the things of ancient days? Who can test himself by the rules and standards which Paul laid down for bishops and presbyters, that they are to be temperate, sober minded, not given to wine, no strikers, apt to teach, blameless in all things, and beyond the reach of the wicked, without finding considerable deflection from the straight line of the rules? What of the regulations of Jesus for his disciples, which He sends them to preach?….that they be men of virtue, so simple and modest and in a word, so heavenly, that the gospel should make its way no less by their character than by their preaching.”

#70

We should remember the condemnation of the scribes and pharisees if we are found more deeply sunken in vice.

#71

Gregory is very depressed about these things. “A man must himself be cleansed before cleansing others: himself become wise, that he may make others wise, become light, and then give light; draw near to God, and so bring others near; be hallowed, then hallow them; be possessed of hands to lead others by the hand, of wisdom to give advice.

# 72

Gregory is worried that people rush into the ministry.

#73

“But this speed in its untrustworthiness and excessive haste, is in danger of being like the seeds which fell upon the rock, and, because they had not depth of earth, sprang up at once, but could not bear even the first heat of the sun…”. You cannot make a priest overnight.

Truly… “Who can mold, as clay-figures are modeled in a single day, the defender of truth, who

is to take his stand with the Angels and give glory with Archangels, and cause the sacrifice to ascend to the altar on high, and share the priesthood of Christ, and renew the creature, and set forth the image, and create inhabitants for the world above, aye and, greatest of all, be God, and make other to be God?”

#74

“I know Whose ministers we are, and where we are placed, and whither we are guides. I know the height of God and the weakness of man, and, on the contrary, his power.

# 76

Gregory feared “to be expounder of truths beyond my power; the majesty and the height, and the dignity, and the pure natures scarce able to contain the brightness of God, Whom the deep covers, Whose secret place is darkness, since He is the purest light which most men cannot approach unto; Who is in all this universe, and again is beyond the universe; Who is all goodness and beyond all goodness; Who enlightens the mind, and escapes the quickness and height of the mind, ever retiring as much as He is apprehended, and by His flight and stealing away when grasped, withdrawing to the things above one who is enamored of Him.” (#77) Such and so great is the object of our longing zeal, and such a man should he be who prepares and conducts souls to their espousals. For myself, I feared to be cast, bound hand and foot, from the bride-chamber

for not having on a wedding garment, and for having rashly intruded among those who there sit at meat. And yet I had been invited from my youth, if I may speak of what most men know not, and had been cast upon Him from the womb, and presented by the promise of my mother, afterwards confirmed in the hour of danger, and my longing grew up with it, and my reason agreed to it, and I gave as an offering my all to Him Who had won me and saved me, my property, my fame, my health, my very words, from which I only gained the advantage of being able to despise them, and of having something in comparison of which I preferred Christ. And the words of God were made as sweet honeycombs to me and I cried after knowledge and lifted up my voice for wisdom.”

He fears the office and yet he is willing to accept it.

#78

Gregory with modesty admits that compared to others he might be better prepared for the pastoral office, but still he claims that this vocation is too high for him. “the commission to guide and govern souls, and before I have rightly learned to submit to a shepherd, or have had my soul duly cleansed, the charge of caring for a flock; especially in times like these, when a man seeing everyone else rushing hither and thither in confusion when the members are at war with one another and the slight remains of love, which once existed, have departed, and priest is a mere empty name….

#79

Controversy and confusion reign in the church. First place in the church is not given to him who fears God, but to him who can best revile his neighbor. We observe each other sins, he says, not to heal them but to aggravate them. A state of chaos reigns like the primeval chaos.

# 82

The state of the priests is no better than that of the people. People are openly at war with the priests.

#84

“We have already been represented on the stage, amid the laughter of the most licentious, and the most popular of all dialogues and scenes is the caricature of a Christian.” (Jay Leno)

#85

How can people contend for Christ in an unchristlike manner?

#86

And yet even now when Christ is invoked the devils tremble, and not even by our ill doing has the power of this Name been extinguished.

#90

Gregory admits that he was too weak for this warfare, “and therefore I turned my back hiding my face in the rout, and sat solitary, because I was filled with bitterness and sought to be silent, understanding that it is an evil time…

#94

In the Old Testament even physical blemishes prevented a man from becoming a priest. No one could presumptuously approach the Holy of Holies. And aware of these things Gregory speaks of his own unworthiness.

#95

“No one us is worthy of the mightiness of God, and the sacrifice, and priesthood, who has not first presented himself to God, a living, holy sacrifice, and set forth the reasonable well pleasing service, and sacrificed to God the sacrifice of praise and the contrite spirit, which is the only sacrifice required of us by the Giver of all; how could I dare to offer to Him the external sacrifice, the antitype of the great mysteries, or cloth myself with the garb and name of priest, before my hands had been consecrated by holy works; before my eyes had been accustomed to gaze safely upon created things, with wonder only for the Creator, and without injury to the creature; before my ear had been sufficiently opened to the instruction of the Lord and He had opened my ear to hear

#99

Who would eagerly accept the appointment to the pastoral office without preparation? “No one, if he will listen to my judgment and accept this advice. This is of all things most to be fear; this is the most extreme of dangers…”

#102

Gregory now says, “Such is the defense which I have been able to make, perhaps at immoderate length for my flight.” But now he is back. His longing for the community at Nazianzus, and his concern about his parents and their weakness and advanced age. (He is stretching it a bit here.)

#112

In the end Gregory was caught between two fears. First was the fear of accepting the office to which he had been ordained, for the many reasons he spoke of. But the second fear was that of disobedience. “My position lies between those who are too bold, or too timid; more timid than those who rush at every position, more bold than those who avoid them all. This is my judgment on the matter”. In the end, he feared to be disobedient.

#116

“If my former conduct deserved blame, my present action merits pardon. What further need is there of words. Here am I, my pastors and fellow-pastors, here am I, thou holy flock, worthy of Christ, the Chief Shepherd; here am I, my father, utterly vanquished and your subject according to the laws of Christ rather than according to those of the land; here is my obedience, reward it with your blessing. Lead me with your prayers, guide me with your words, establish me with your spirit. Such is my defense.