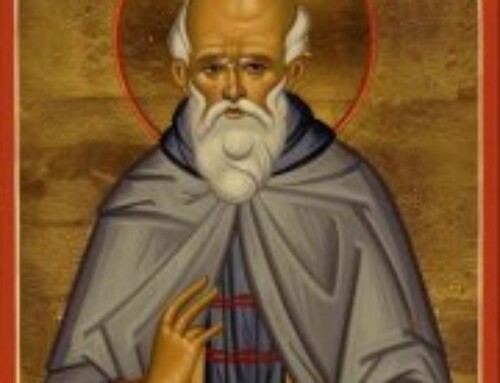

Pope Gregory The Great (Gregory ho Dialogus) 540-604

(Gregory: The Man of Balance)

The Pastoral Rule

Introduction

The fourth of our patristic commentaries on the pastoral life, that of Pope Gregory I of Rome was written in the sixth century, some two centuries later than those of Gregory The Theologian and John Chrysostom. This commentary was written in the West, although Gregory wrote at least a small part of it in Constantinople.

Sixth century Italy (as virtually all Western Europe) was not a happy place. The so called Barbarian Invasions were radically changing the Imperial order in Western Europe. Already in the 400s Italy was fundamentally changed. The last Western Roman Emperor had been overthrown in 476 AD. In 488 the Ostrogoths had invaded Italy. Ravenna was taken by the Ostrogoths in 493. In 527 Emperor Justinian comes to power in Constantinople. He tries to reassert the Byzantine authority in Italy and the west. Shortly after his death in 568, The

Lombards conquered northern Italy.

Many of the barbarians who entered Western Europe came as Arians. The Visigoths in Spain were Arian as were the Lombards. The exception was the Franks. In 496 King Clovis was baptized as a Catholic. The pagan Anglo Saxons had invaded England in 451. The British Christians were driven into what today is Wales.

In the sixth century there are some rays of hope. The Franks were Catholic. The Visigoths of

Spain formally left Arianism and became Catholic at the Synod of Toledo in 598 under King

Reccared. (Here comes the Filioque) This was the world inherited by Pope Gregory I. In

Rome the old civil government had broken down. Gregory would be challenged in ways few

popes have ever been challenged.

Born in c. 540 AD, Pope Gregory I (aka Gregory Dialogus) came from a family of senatorial rank in Rome. At least one member of this family had already served as a pope. At the age of 32 Gregory became the civil Prefect of Rome. Several years later, in 575 AD at the death of his father, Gregory left the imperial service and chose the monastic life. (Here we go again.) He turned his family home into a monastery. He also built six more monasteries on his family estate in Sicily. After living the monastic life in a very austere form, Gregory was asked by Pope Pelagius II to become his representative in Constantinople in 579 AD. A position he held for about six years. Gregory continued to live the monastic life in Constantinople. Although he became acquainted with the important people of Constantinople, Gregory claims that did not learn Greek.

Sixth century Italy was in dire straits. It was being overrun by the Lombards. Gregory was not

able to get the help he wanted from Constantinople. After his recall to Rome, Gregory returned

to his monastery but remained an advisor to Pelagius II. Upon the death of Pelagius, Gregory, who was a deacon at the time, was elected as pope. Gregory would have preferred to have remained in his monastery, but he rose to become one of the greatest popes. He was the first monastic pope.

When he ascended to the papacy the civil government of Rome had broken down. Famine, pestilence and the Lombards were in control. Gregory took over the city, spiritually and materially. He preached repentance in the face of a plague and provided food for the starving of the city. He reorganized the papal properties in Italy, Africa and Dalmatia. He organized the defense of the city, paid the army and appointed generals. He brought about reforms in the church. He established strong links with the churches of Spain (which was leaving Arianism in 589 and becoming Catholic) and Gaul (which was plagued with a host of heresies). He sent missionary monks to England to convert the Anglo Saxons. He did not like Canon 28 of Chalcedon which gave the title of Ecumenical Patriarch to Constantinople. He was a strong defender of rights of the papacy. He has been called the father of the medieval papacy.

Among his writings that survive are 850 letters, His Dialogues, his Exposition on Job, (with its threefold sense of scripture: the literal, mystical and especially moral sense), and his famous Pastoral Rule.

The Pastoral Rule

At the very beginning of his papacy Pope Gregory wrote the document that is known by two names. It is known as The Book of Pastoral Rule (Liber Regulae Pastoralis) and also as The Book Of Pastoral Care (Liber Pastoralis Curae). The title Book of Pastoral Rule is the way Gregory refers to the document in his letter to Bishop Leander of Seville, to whom the book was originally sent. The title, Book of Pastoral Care comes from the opening words of the document. The book was addressed to John, Bishop of Ravenna. The terms Pastoral Rule and Pastoral Care give us an insight into how Gregory saw the Pastoral Office, (ruler and caregiver?) which in this instance is the office of the bishop. (Although it was clearly written for the bishop, a large amount of what he writes is applicable to the pastoral work of the priest as well.) In an earlier work, his Commentary on the Book of Job, which he wrote in Constantinople, Gregory sketches a plan the Pastoral Rule. This is actually the prologue to Book Three of the Pastoral Rule.

As Gregory tells Leander of Seville, he wrote this work at the very beginning of his papacy. He comes from a background in civil administration, papal diplomacy, papal advisor, monk and deacon. He did not serve as a priest or bishop prior to becoming the Bishop of Rome.

The Pastoral Rule was well accepted in Gregory’s own lifetime. The Patriarch of Antioch, at the request of the Byzantine Emperor (Maurice), translated the book into Greek. It was taken to England by Gregory’s missionary Augustine of Canterbury where 300 years later it was translated and paraphrased in the West Saxon language at the request of King Alfred the Great, who apparently sent a copy to every bishop in his kingdom. In the later Carolingian kingdom, a copy was given to each bishop at his consecration.

There is no question that Pope Gregory is indebted to Gregory The Theologian. In fact Pope Gregory admits this. Part Three of the work actually develops the pastoral approach begun by the earlier Gregory. As Pope Gregory says, “Since…, we have shown what manner of man the pastor ought to be, let us now set forth after what manner he should teach. For as long before us Gregory Nazianzen of reverend memory has taught, one and the same exhortation does not suit all…” He then, as we will see, goes on to develop this approach to pastoral work which had already been formulated by Gregory the Theologian.

Introduction

The Pastoral Rule consists of four parts. (The translation in the Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers refers to them as Part One, Two, Three and Four.)

Part one addresses the question of “who” should take on the pastoral rule in the Church; it consists of eleven chapters.

Part Two, which also consists of eleven chapters, discusses the “lift” of the Pastor, and the moral qualities he must have.

Part Three, by far the longest part of the book, addresses “How the ruler, while living well (righteously), ought to teach and admonish those that are put under him”. The bishop is the admonisher and teacher of the community. Part Three of the Rule tells him how to carry out this ministry. What follows is a series of Admonitions. There are 36 Admonitions which instruct the pastor how to deal with people. Each of the Admonitions takes the form of comparisons. Each Admonition begins with the words “Differently to be admonished are….” for example “the poor and the rich”; “men and women”; “celibates and married people” and so forth. Most of the document is an instruction not about the sacramental ministry of the pastor, but on how he is to deal with people. And how they are to be taught and led.

Part Four of the Pastoral Rule is a very brief chapter on the importance of self examination on the part of the pastor.

Part One (Who should hold the position of Pastor or Bishop?)

As Pope Gregory begins his treatise he notes that John of Ravenna had reproved him for wanting to hide from the burdens of pastoral care. It is interesting that our three prominent authors on the pastoral life each begin their treatise and their pastoral life by explaining why they had initially avoided the pastoral office.

Gregory now will express his feelings about the pastoral office which is a heavy burden. He writes this so that anyone who might be free from such responsibility might “not unwarily seek them and that he who has so sought them may tremble for having got them.”

Gregory then explains how he has written his instruction in four parts. “We must consider after what manner every one should come to supreme rule (bishop); and duly arriving at it, after what manner he should live; and living well, after what manner he should teach; and teaching aright, with how great consideration every day he should become aware of his own infirmity….”

Part One, Chapter I

“No one” Gregory says, “presumes to teach an art till he has first, with intent meditation, learnt it. What rashness is it, then, for the unskillful to assume pastoral authority, since the government of souls is the art of arts! For who can be ignorant that the sores of the thoughts of men are more occult than the sores of the bowels?” (GT) And, he says, “How often do men who have no knowledge of spiritual precepts fearlessly profess themselves physicians of the heart….” They want to be teachers and rulers and they covet superiority to others. Some who are totally unfit have become pastors. Ironically, “this unskillful ness of the shepherds doubtless suits the wishes of those they rule….the blind leading the blind.

The bishop is then, the physician, the teacher, the ruler. He must not be a novice in these matters.

Chapter 2

Some, while intellectually prepared… “who have investigated spiritual precepts with cunning care”…”.and (then) what they have penetrated with their understanding they trample on in their lives.” What they preach with their words, they deny with their lives. “No one” he says, “does more harm in the church than the one who had the name and rank of sanctity, while he acts perversely.” Unfortunately no one takes him to task. And out of reverence for his rank, the sinner is honored. Such a person should fly from the pastoral office considering what the Lord said about scandalizing the little ones who believe in him.

The pastor must not only understand the mysteries of faith. He must live them. He must not be a fraud. If he is anything less, out of fear he should run from the office.

Chapter 3

The next issue is the desire for honors.

No one who is unequal to the office or who through a desire for preeminence should dare to become a pastor. Consider the example of Christ himself He (who) could have reigned over men if he chose, chose not to do so, giving an example to all men. He avoided glory, honor, prosperity and preeminence, choosing rather the cross. Even when a man has learned humility in the school of adversity, if he comes to a position of power and authority, he becomes changed and elated by his familiarity with glory.

The virtue of humility will be severely tested in the life of anyone who holds authority.

Chapter 4

In chapter 4 Gregory becomes very practical. Here Gregory seems to be saying that those in positions of authority end up with “too much on their mind”. “Often the care of government when undertaken, distracts the heart in diverse directions; and one is found unequal to dealing with particular things, while with confused mind divided among many (things).” He then quotes Ecclesiastes “My son, meddle not with many matters.” (I think Pope Gregory is really on to something here. As priests we find ourselves trying to do a hundred things at the same time. Have you ever noticed the typical priest’s desk and office? Mine is a mess. I can assure you that I have had a “confused and divided mind” on many a day.

Chapter 5

There are some men who actually are very capable of ruling in the church but they run away from it and not always for the highest of motives. “They are” he says “exalted by great gifts, who are pure in zeal for chastity, strong in the might of abstinence, filled with the feasts of doctrine (i.e., good theologians) humble in the long-suffering of patience, erect in the fortitude of authority, tender in the grace of loving kindness, strict in the severity of justice.” And when called they refuse to undertake the supreme office or rule. They forget that the gifts they have received were not just for themselves, but for the good of other people. And so, these men are ardent for the studies of contemplation only, and they shrink from serving their neighbor by preaching.

“….they long for a secret place of quiet, then long for a retreat for speculation…” (Have we heard these words before?) These Gregory judges harshly. He says that “they are guilty in proportion to the greatness of the gifts whereby they might have been publicly useful.”

Chapter 6

And if a man claim humility as a reason for not taking on the office of pastor, then true humility would mean that the man should not reject what the church asks him to do

Chapter 7

In chapter seven Gregory looks at the pastoral office from the perspective of the preacher. The man who accepts the office of pastor must know something about preaching. Some he says are drawn to preaching for praiseworthy reasons. But sometimes we find people that are drawn to it by kind of compulsion. In modern times these are the people who volunteer to speak at the funerals of their friends.

There are in the church the Isaiah’s who say “here am I Lord send me” and the Jeremiah’s who say “Ah Lord, I cannot speak”. These holy men were motivated by the right reasons. Isaiah had his lips purged and Jeremiah eventually did what the Lord commanded him. Here I think we have to examine our own personal motivation for preaching. Do we see it as an important part of our ministry? Do we see ourselves as servants of God’s Word or are we preaching our own words?

Chapter 8

About those who seek higher office for unworthy motives, Gregory says that “for the most part those who covet preeminence seize on the language of the Apostle where he says… “If a man desires the office of a bishop, he desireth a good work”. That, he says is absolutely true. But we must not forget that at that time the bishops were the first ones “to be led to the torments of martyrdom.” “And therefore it was laudable to seek the office of a bishop, since through it there was no doubt that a man would come in the end to heavier pains.” We do not have too many people volunteering for martyrdom.

Chapter 9

Pope Gregory is a pretty good psychologist. He shows us a profound insight into the dynamics of human motivation. We sometimes fool ourselves into believing that we have the best of intentions when we set out to do something. He says “for the most part those who covet pastoral authority mentally propose to themselves some good works besides, and, though desiring it with a motive of pride, still muse how they will effect great things: and so it comes to pass that the motive suppressed in the depths of the heart is one thing, another what the surface of thought presents to the muser’s mind.”

Such a man will eventually forget his good intentions and be taken over by pride. It is very hard to learn humility in high places. Examine your past life, he says, and see if you have been able to learn humility and not be flattered by praise. Do not forget that as a prelate, you are going as a physician to your people. Be sure that you are not sick yourself

Chapter 10.

Gregory now concludes Part One of the Pastoral Rule by summarizing the characteristics of the man who should rule and also the characteristics of the man who should not rule.

The man who should rule is one who: is already living an exemplary spiritual life. He must be one who dies to his own passions of the flesh; who disregards worldly prosperity; who is not afraid of adversity; who desires only inward wealth; who is not thwarted from his work by the frailty of his body; he must not be one who covets things; but one who freely gives away his own possessions; he must be quick to be compassionate and pardon, but on the other hand he must not “bend down from the fortress of rectitude (or righteousness); he must not perpetrate evil deeds; he must sympathize with the infirmity of other people, and rejoice in the good of his neighbor as those it was his own. He should have nothing to blush for in his past life; he must be one who

studies…. so that he may water the dry hearts with the streams of doctrine; he must be a man of prayer…. “One who has already learned by the use and trial of prayer that he can obtain what he has requested from the Lord….”; if you are going to intercede with God for your people, you have to be on familiar terms with God. It is very dangerous to trying to appease the wrath of God for other people when you are on bad terms with God to start with yourself

Chapter 11

The man who should not come to the rule.

“Wherefore let every one measure himself wisely, lest he venture to assume a place of rule, while in himself vice still reigns unto condemnation; lest one whom his own guilt depraves desire to become an intercessor for the faults of others.” Very simply the man coming to the pastoral office cannot live a life filled with vices.

Gregory quotes a text from the Book of Leviticus reminding Christian priests that in the Old Testament times even a physical blemish was enough to disqualify you for the priesthood. Here is the text “If he be blind, if he be lame, he have either a small or a large and crooked nose, if he be broken-footed or broken-handed, if he be hunchbacked, if he be bleareyed, if he have a white speck in his eye, if he have chronic scabies, if impetigo in his body, or if he be ruptured….” These were disqualified.

Gregory then goes on to interpret this text in rather unusual way. It becomes an allegory. Each of these physical blemishes is a sign of some spiritual failing. The blind man is unacquainted with spiritual contemplation; the lame man cannot walk in the way of the Lord, and so forth. His interpretation of the large nose leaves me a bit puzzled. He says “For a large and crooked nose is excessive subtlety of discernment, which, having become unduly excrescent (meaning it protrudes out too far and is too big), itself confuses the correctness of its own operation.”

PART TWO: ON THE LIFE OF THE PASTOR

In Part One, Gregory has already told us of the kind of person that should approach (or avoid) the pastoral office. He must come with the virtues listed above. But he must also develop specific virtues needed for his pastoral work. Perhaps we might call them “pastoral virtues”.

CHAPTER 1

In Chapter One of the Second Part of the Pastoral Rule, Pope Gregory sets forth what the life of the pastor should be. He lists some ten virtues that the pastor must have, and having listed them, he then goes on in ten successive chapters to comment on each. Here are his opening words:

“The conduct of a prelate ought so far to transcend the conduct of the people as the life of shepherd is wont to exalt him above the flock. For one whose estimation is such that the people are called his flock is bound anxiously to consider what great necessity is laid upon him to maintain rectitude. It is necessary, then, that in thought he should be pure, in action chief, discreet in keeping silence, profitable in speech; a near neighbor to everyone in sympathy, exalted above all in contemplation; a familiar friend of those who live rightly through humility, unbending against the vices of evil-doers through zeal for righteousness; not relaxing in his care for what is inward from being occupied in outward things, nor neglecting to provide for outward things in his solicitude for what is inward. But the things we have thus briefly touched on let us now unfold and discuss more at length.”

Chapter 2

Gregory begins with the issue of purity of thought. “Lax cogitations (loose thoughts) should by no means possess the priestly heart.” Pope Gregory is indeed a wise man. When we consider this admonition, every thing that we do, either good or evil, begins with our thoughts. We will never do something that we have not thought about previously. It is a most wise warning. Guard your thoughts and you will avoid many problems. Just don’t let yourself think certain thoughts.

Chapter 3

The ruler should be always be chief in action, meaning that he must be the first to do what is right. “That by his living he may point the way of life to those that are under him, and that the flock, which follows the voice and manners of the shepherd, may learn how to walk better through example than through words. Very simply he has to be a model for those he leads.

Chapter 4

The ruler should be discreet in keeping silence and profitable in speech. Here he must be wise enough to suppress what ought to be suppressed but he should not suppress what should be said. “For as incautious speaking leads to error, so indiscreet silence leaves in error those who might have been instructed. Some shrink from doing this fearing to lose human favor. “Whoever enters the priesthood undertakes the office of a herald, so as to walk, himself crying aloud, before the coming of the judge who follows terribly.” What a powerful image of the minister of the Word!

Chapter 5

In his compassion, (and compassion means to suffer with someone) the ruler should be a near neighbor to everyone, but exalted above others in their contemplation. The pastor has to be able to be close to any human situation and yet he must pursue a spiritual life which ascends from the lowly human condition to heaven. Paul could speak about the problems of human sexuality on the one hand and be caught up to Paradise on the other. Moses could enter the holy of holies and yet carry the burdens of the ordinary people.

Chapter 6

The pastor will find that he will be living among people who live rightly and others who do not. In the presence of those who live good lives, he must be a companion, out of humility. In their presence he waives his rank and counts them as his equals. But against the vices of the evil he must be rigid. The pastor must be humble. “Supreme rule” Gregory says “is ordered well, when he who presides lords it over vices, rather than over his brethren.” The ruler should be like a mother in kindness and like a father in discipline. Gentleness is to be mingled with severity. The rod is both for striking and for supporting.

Chapter 7

In Chapter 7 Pope Gregory brings up one of the most important issues in the life of any pastor. We might sum it up as the balance between the interior spiritual concerns of the pastor and the external material concerns. Gregory recognized the basic tension that exists in the life of any pastor. It is a matter of taking care of the one, and not neglecting the other. The temptation that most fall to is being too preoccupied with temporal matters.

“The ruler” he says “should not relax his care for the things that are within his occupation among the things that are without, nor neglect to provide for the things that are without in his solicitude for the things that are within…”

Very often the pastor is delighted to be involved in temporal matters. “For it is often the case” he says “that some, as if forgetting that they have been put over their brethren for their souls sake, devote themselves with the whole effort of their heart to secular concerns; these, when they are at hand, they exult in transacting, and, even when there is a lack of them, pant after them day and night with seethings of turbid (cloudy or muddy) thought; and when, haply they have quiet from them, by their very quiet they are wearied all the more. For they count it pleasure to be tired by action; they esteem it labour not to labour in earthly business…” (tangible rewards can be very satisfying)

This pastor does not teach his people exhorting their minds and chastising them. When earthly pursuits occupy the pastor’s mind, “dust, driven by the wind of temptation, blinds the church’s eyes.” No man can serve two masters. “Secular employments, therefore, though they may sometimes be endured out of compassion, should never be sought after out of affection for the things themselves.”

But Gregory also sees the other side of the issue. What about a pastor who does not, as we say today “live in the real world”. “There are some” he says, “who undertake the care of the flock, but desire to be at leisure for their own spiritual concerns as to be in no wise occupied with external things.”

The preaching of these pastors is going to be despised, because while they may preach and point out the faults of others, they may ignore the fact that the people they are preaching to may not even have the necessities of life. Unless these people see the hand of compassion on the part of the preacher, their minds will never be penetrated by the truth of his preaching. The point here is that the pastor must never become so preoccupied with temporal matters that he forgets his primary responsibility, but on the other hand, he must not live a life so taken up with his own spirituality that he fails to see the needs of others.

Chapter 8

Gregory now moves on to a problem that has plagued pastors throughout the ages. This is the issue of constantly trying to “please men”. He seeks to be beloved of those who are under his care, more than he seeks the truth. We all want to be liked. Here Gregory uses the scripture in a most fascinating way. He reminds the pastor that Jesus Christ is the Bridegroom and the Church is His bride. The pastor is actually a servant whom the Bridegroom has sent to bring gifts to His bride. This servant would be guilty of treacherous thought if he, as the servant, tries to please the eyes of the bride. The Church is not our bride, it is Christ’s.

The pastor does not chastise the people lest their affection for him grow dull. Sometimes “he smoothes down with flatteries the offense of his subordinates which he ought to have rebuked.”

On the other hand, “it is to be borne in mind also, that it is right for good rulers to desire to please men; but this is in order to draw their neighbors by the sweetness of their own character to affection for the truth; not that they should long to be loved for themselves, but should make affection for themselves as a sort of road by which to lead the hearts of their hearers to the love of the Creator. For it is indeed difficult for a preacher who is not loved, however well he may preach, to be willingly listened to.”

Chapter 9

Chapters 9 and 10 deal with the question of how the pastor should deal with vices in the lives of his people. (This topic will take up the major part of the book). But here he gives us his basic pastoral approach. First, have the wisdom to realize that sometimes what look like virtues may indeed be vices. For example, the one who claims to be frugal may actually be a cheapskate. We all have met a few of these folks.

Chapter 10

But when faced with vices and sin, Gregory tells us that at times it is important to be “seasonably tolerant” with the sinner. What he means here is that although we may be aware of an evil or a sin, we may not be able to say anything about it immediately. “For sores being unseasonably cut are the worse enflamed.” When the right moment comes along, usually in private then it is time to say something. If you speak at the wrong time you may find yourself saying things in a way you might later regret.

Chapter 11

The preacher will carry out his responsibility if, with the fear of God, and love, he meditates each day on the sacred scriptures. As Paul said to Timothy, “Till I come, give attendance to reading”. Be knowledgeable about Holy Scriptures, especially the gospels, because when people come with questions, you should be prepared to answer their questions and not have to go home and find the answers.

With these remarks Gregory concludes Part Two which has addressed the question of the life of the Pastor. He now turns to the question “How the ruler, while living well (meaning righteously) ought to teach and admonish those that are put under him.

PART THREE

Part Three of the Pastoral Rule takes up two thirds of the entire book

(The final section, PART FOUR is only two pages. Here after discussing the active life of the pastor brings him back into himself)

Part three consists of 40 chapters. It is a series of “admonitions” or instructions to the pastor on how he should treat people of differing categories.

Pope Gregory begins with a Prologue in which he admits his indebtedness to Gregory the Theologian:

Since, then we have shown what manner of man the pastor out to be, let us now set forth after what manner he should teach. For, as long before us, Gregory Nazianzen of reverend memory has taught, one and the same exhortation does not suit all, inasmuch as neither are all bound together by similarity of character. For the things that profit some often hurt others; seeing that also for the most part which nourish some animals are fatal to others and the bread which invigorates the strong kills little children. Therefore according to the quality of the hearers ought the discourse of the teachers to be fashioned, so as to suit all and each for their several needs, and yet never deviate from the art of common edification.

Chapter 1

Gregory now lists the different kind of people that the pastor must deal with and how he must discriminate between the various groups: He begins by saying “Differently to be admonished are these that follow:” (This is how he will begin each of his Admonitions)

Men and women; poor and rich; joyful and sad; prelates and their subordinates; servants and masters; the wise and the dull; the impudent and the bashful; the forward and the fainthearted; the impatient and the patient; the kindly disposed and the envious; the simple and the insincere; the well person and the sick; those who fear scourges and those who have grown so hard in iniquity as not to be corrected by scourges; the quiet and those who talk too much; the slothful and the hasty; the meek and the passionate; the humble and the proud; the obstinate and the fickle; the generous and the stingy; the lovers of strife and the peacemakers; those who do not understand the sacred law, and those who speak about it without humility; those who actually could preach, but refuse because of their humility, and those whom imperfection or age (young?, old?) should not preach, but in their rashness they feel compelled to do so; those who are successful in worldly matters, and those who covet things but are unsuccessful; those who are bound by wedlock, and those who are free from the ties of wedlock; those who have had the experience of carnal intercourse, and those are ignorant of it; those who deplore sins of deed, and those who deplore sins of thought; those who bewail their misdeeds, but keep on doing them, and those who have given up their misdeeds but don’t bewail them; those who actually praise their own misdeeds, and those who may condemn their misdeeds but keep on doing them; those who are overcome by sudden passion, and those who act with premeditation; those who often sin in small ways, and those who do not sin often, but sin in very serious ways; those who never even begin to do good deeds, and those who never seem to finish what they begin; those who sin in secret and do good publicly; and those who do their good deeds in secret and permit their faults to be known.

“What profit is it for us to run through all these things collected together in a list, unless we also set forth, with all possible brevity, the modes of admonition for each?

And that is exactly what he does. Some admonitions are very brief and to the point, while with others he takes his time. (It would not be possible to comment on all the various admonitions, but we can look at least a few.)

Admonition I

Gregory begins with men and women. “Differently, then, are to be admonished are men and women; because on the former (the men) heavier injunctions, on the latter (women) lighter are to be laid. That those may be exercised by great things, but these winningly converted by light ones.” Gregory is talking about “injunctions” or admonitions. In serious matters you have to talk to men in a different way than you talk to women.

Admonition 2

In like manner you can’t admonish the old in the way you might admonish a young person. Severity might help the young to improve; but with older people you will have to exercise kindness. “Rebuke not the elder, but entreat him as a father.” I Tim. V 1)

Admonition 4

Gregory admits that people have different temperaments. Some are usually happy while others are often depressed. “Different”, he says, to be admonished are the joyful and the sad…. before the joyful are to be set the sad things that follow upon punishments; but before sad the promised glad things of the kingdom. “Some are not made joyful or sad by circumstances, but are so by temperament. And to such it should be intimated that certain defects are connected with certain temperaments; that the joyful have lechery close at hand, and the sad wrath. Hence it is necessary for every one to consider not only what he suffers from his particular temperament, but also what worse things press on him in connection with it….”

Admonition 5

The next admonition is for those in high authority in the church. Here he distinguishes how differently one must admonish a prelate, and how one admonishes one subject to authority. The prelate should not command more to be fulfilled than is just; and the subject, that he submits with humility. Those in authority should model themselves after the “living creatures” from Ezekiel who have eyes round about and within. Those in authority must with “circumspection… have eyes with and without.” Subjects should not rashly judge their superiors. We should not offend against those who are set over us, for if we do so, we go against the ordinances of Him who set them over us.

Admonition 7

Every pastor comes across people that are bright and knowledgeable, and those who are not so bright. To those who are brilliant, especially in worldly matters, the pastor must tell them to “leave off knowing what they know….” (“Hey Father, the church is a business, let me tell you what we should do.”) The dull should be told to seek out what they do not know. The brilliant might think themselves wise. As St. Paul says in I Cor 111.18 “If any man seemeth to be wise in this world, let him become a fool, that he be wise”.

Admonition 8

If you are dealing with someone who is really impudent, “nothing but hard rebukes restrains him from vice. The timid and the bashful can be corrected by gentle reminders”.

Admonition 10

Some people seem to bubble over with enthusiasm while others are very patient. Each must be dealt with differently. The hurried must be told that they might be carried away headlong by human emotions and find themselves in situations that they did not plan for. They might find themselves doing evil things that they might not be aware of. On the other hand patient people may be able to suffer difficult situations for a long time, but, they might actually be in jeopardy of negating the good they do with their patience but actually coming to hate those who trouble them. Unless patience is followed with love, it can be turned into hatred and seeking after vengeance.

Admonition 11

Some people praise good deeds and virtue, but unfortunately while they esteem these things they don’t act accordingly.

Admonition 12

Other people are crafty and insincere. Gregory advises the pastor to remind these sorts of people of how very difficult it is to be a good liar and consistently insincere. “…the insincere are to be admonished to learn how heavy is the labor of duplicity, which with guilt they endure.” (Liars have to have perfect memories.) “There is” insists Gregory “nothing safer for defense than sincerity, not easier to say than the truth.”

Admonition 13

Those who enjoy good health must be reminded that good health is a gift. This gift should be used to gain the health of the soul. Good health should not be used for an occasion of sin. It is a precious gift that can be lost. The health of the flesh can be lost through vices; the flesh then is worn with afflictions. On the other hand, those who are sick should be firm in their belief that they are sons of God. They should remember the great sufferings that the Lord endured for our salvation.

Admonition 15

There are those who are overly silent and those who talk too much. To the overly silent Gregory would say that they may well suffer from what he calls “loquacity of the heart”. “Thoughts seethe the more in the mind…” This man is exalted into pride by his ability to remain silent. And pride leads to all other vices. Their pain can be like a closed up sore that pains all the more. On the other hand, idle words and too much speaking can lead to hurtful words.

Admonition 17

Differently to be admonished are the meek and the passionate. When the meek come to authority they suffer from a kind of sloth. At first they are too lax; but this can eventually lead to be strict beyond need. On the other than, the passionate are swept up in a frenzy of mind by the impulse of anger. They turn the lives of the subjects into utter confusion.

Admonition 20

Pastors have to deal with both the glutton and the abstinent. Those who eat too much find themselves being carried away by talking too much, by levity of conduct, and the stings of lust are excited. The one who abstain may find himself being impatient, and guilty of pride. For those who eat too much, they should remember the rich man in the story of Lazarus. When he got to hell, it was his tongue that suffered most. Jeremiah reminds us that it was “the chief of cooks that broke down the walls of Jerusalem.” And according to Gregory, the chief of cooks is the belly. The virtue of abstinence is actually a “small virtue”. “For a man fasts not to God but to himself, if what he withholds from his belly for a time he gives not to the needy, but keep to be offered afterwards to his belly.”

Admonition 24

In Admonition 24, Gregory speaks of people that are probably familiar to pastors of every age. Here he speaks of “sowers of strife” on the one hand and “peacemakers” on the other. Sowers of strife should be reminded just who it is they are following. They are disciples of the apostate angel himself. But peacemakers should be aware it is possible for them to be making peace among people that it is better not to make peace between. Unity between people who do good is very desirable, but unity among those who do evil is quite another thing.

Admonition 28

Admonition 28 speaks of how the pastor must treat the married differently from the single. The married must be reminded that as they seek to please one another, they must not forget to please God. “Husbands and wives are to be admonished to remember that they are joined together for the sake of producing offspring; and, when giving themselves to immoderate intercourse, they transfer the occasion of procreation to the service of pleasure….they may actually “exceed the just dues of wedlock”.

The single are to be reminded that they are not bound by wedlock. They observe heavenly precepts all the more closely in that no yoke of carnal union bows them down to earthly cares. They are not bound by the many earthly cares of the married. More is expected of them. But if they suffer from the storms of temptation with risk to their safety, they should seek the port of wedlock.

Admonition 29

For those unmarried persons who have committed sins of the flesh, they should be reminded of the great benevolence of God and the bosom of His pity toward us. Those who have preserved virtue should be should be told to fear falling into sin.

Finally, in your preaching the pastor should not preach deep subjects to weak souls; and most important it is more important to preach by the quality of your life than it is with your words. (Those interested may read all the various admonitions.)

PART IV The Conclusion: Time For Self Examination

The pastor or preacher, if is successful, may find that “the mind of the speaker is elevated in itself by a hidden delight in self-display”…..

“But since often, when preaching is abundantly poured forth in fitting ways, the mind of the speaker is elevated in itself by a hidden delight in self-display, great care is needed that he may gnaw himself with the laceration of fear, lest he who recalls the diseases of others to health by remedies should himself swell through neglect of his own health; lest in helping others he desert himself, lest in lifting up others he fall. For to some the greatness of their virtue has often been the occasion of their perdition; causing them, while inordinately secure in confidence of strength, to die unexpectedly through negligence. For virtue strives with vices; the mind flatters itself with a certain delight in it; and it comes to pass that the soul of a well-doer casts aside the fear of its circumspection, and rests secure in self-confidence; and to it, now torpid (dormant-dead in the water), the cunning seducer enumerates all things that it has done well, and exalts it in swelling thoughts as though superexcellent beyond all beside. When it is brought about, that before the eyes of the just judge the memory of virtue is a pitfall for the soul; because, in calling to mind what it has done well, while it lifts itself up in its own eyes, it falls before the author of humility.” In other words, if you do something good, for your sake – not God’s – give God the glory.

Now he concludes:

“See now, good man, how, compelled by the necessity laid upon me by thy reproof, being intent on showing what a Pastor ought to be, I have been as an ill-favored painter portraying a handsome man; and how I direct others to the shore of perfection, while myself still tossed among the waves of transgressions. But in the shipwreck of this present life sustain me; I beseech thee, by the plank of thy prayer, that, since my own weight sinks me down, the hand of thy merit may raise me up?