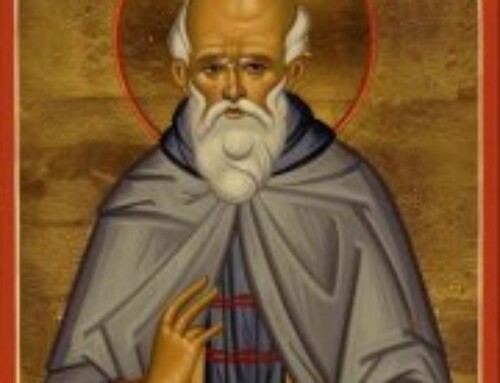

John Chrysostom 347-407

On The Priesthood

John Chrysostom is among the most well known saints of the Eastern Church. He was born in Antioch in c. 347 and died in exile in 407 as the Patriarch of Constantinople. He was educated in both law under the pagan Libanius and in theology by Diodore of Tarsus, a fellow Antiochian. He embraced the monastic life as a young man. He became a priest in 386 when he was almost

40. He gained fame as a preacher in Antioch from 386 to 398 when against his wishes he was elevated to Patriarch of Constantinople His efforts at reforming the clergy, the laity and the court made him the enemy of many. He was deposed by the Synod of the Oak in 403 (on trumped up charges of being an Origenist and eating lozenges in church); but was recalled only to be banished once more and to die in exile in 407.

His Treatise on the Priesthood is probably his best known work. According to J.N.D. Kelly it was written sometime around the year 390 when St. John Chrysostom was in his early 40s.

Treatise On The Priesthood

The Treatise On The Priesthood takes the form a dialogue between John Chrysostom and his mysterious friend Basil whose identity is unclear. The dialogue is an explanation of why John Chrysostom had in certain sense “let down” his friend Basil, and why John Chrysostom (at that point in his life) had avoided ordination. Basil and John Chrysostom were both young men who heard rumors that they were going to be ordained, probably as priests (possibly as bishops). St. John Chrysostom and Basil came to an understanding that if one were ordained they both would be ordained. Either way, they would act in consort. But this is not what happened. Basil was, as it were “caught” and ordained; while John Chrysostom fled and hid. Sometime later Basil comes to John extremely distraught. Basil is astonished at what his friend had done. John Chrysostom seems to think that what he has done has some humor in it. Basil clearly feels otherwise.

In the edition published by St. Vladimir Seminary Press by Graham Neville, it is stated some modern commentators regard the whole episode between Basil and John as fictitious. Basil is simply a literary figure who has no historical existence. This “work of fiction” gives St. John Chrysostom an opportunity to write about the priesthood. Neville does not accept this and neither do I. If there were no truth to what he wrote, how would he have gotten away with it? For the purposes of my comments, I am simply going to accept the document as having a basis in historical fact.

Some are troubled by what might be called the “pious fraud” carried out by St. John Chrysostom in being less than honest with his friend Basil. Again, I will leave this issue to others. For our purposes, it is more important to discover what this fourth century Father may have to say about the priesthood.

Why then did he write this treatise? It may have been that later in his life there were some lingering doubts about why John Chrysostom had not initially accepted ordination. This treatise may have been written to explain his earlier reluctance in being ordained.

St. John Chrysostom’s work on the priesthood has, as Kelly says, “many points of contact with, and has been strongly influenced by, the discourse of Gregory the Theologian. Gregory’s work was also an explanation of why he too ran away from the priesthood; although in his case, he had already been forcibly ordained by his father. Although the work in some way is indebted to Gregory the Theologian, John Chrysostom was very original, more so that the later Pope Gregory, who as we will see is very much, affected by Gregory the Theologian.

ON THE PRIESTHOOD

The treatise On The Priesthood is divided into six books. This is the form that is given in the Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers Series, (First Series Vol. 9). The translation of Graham Neville which is published by St. Vladimir Seminary Press divides the treatise into 16 chapters. (I would also add that Neville gives a comparison of the three major works on the pastoral office, John Chrysostom, Gregory the Theologian, and Pope Gregory I in the introduction to his translation of John Chrysostom.)

Book I

Book I begins with John Chrysostom‘s statement about his friendship for Basil, whom he says “excelled all other friendships”. Basil and John Chrysostom were engaged in the same studies under the same teachers. Their lives took the same direction after their studies. They were social equals. They shared a common interest in monasticism, but here John Chrysostom says, Basil moved ahead, while he was still entangled in worldly concerns, frequenting the law courts, the

theatre and the market place. Basil urged John Chrysostom to join him in a common life of

monasticism, by living together. And in time John Chrysostom did move away from his worldly

concerns. At this point John Chrysostom’s mother steps in and asks John Chrysostom not to leave her. In a very touching scene she takes her son into her bedroom and sits him on the bed on which she had given birth to him, pleads that he will not leave her. Since the death of her husband–which occurred when she was a very young woman—- her life has been extremely difficult raising her children and managing the affairs of the family. She asks him to wait until after her death when he can pursue any course that he wishes. His friend Basil only encourages him the more.

The dialogue then takes a turning point. John Chrysostom was still unwilling to join Basil, when he says “a report suddenly reach(ed) us that we were about to be advanced to the dignity of (the priesthood/the episcopate). As soon as I heard this rumor I was seized with alarm and perplexity: with alarm lest I should be made captive against my will…..” Basil comes to John Chrysostom and asks that they agree to follow the same course of action, whether fleeing, or submitting to be captured. Although John Chrysostom agrees to do whatever Basil did, John Chrysostom has other plans. He does not want the church to be deprived of the services of such a qualified person as Basil. He permits Basil to be captured and ordained, while he runs away and hides. Basil does not want to be ordained. His captures lie and tell him that John Chrysostom had already submitted. Basil is ordained.

When Basil becomes aware of John Chrysostom’s duplicity, he comes to him and is so upset

that at first he cannot even speak, so great was the violence done to him. Tears and grief prevent

Basil from speaking. John Chrysostom, realizing the he was the cause of this, laughs for joy!

And kissed his hand.

Basil informs John Chrysostom that people are of the opinion that John Chrysostom rejected the priesthood out of vainglory. Everyone is talking about him. Basil is too ashamed to tell people the truth of what had happened. “How” he asks can he offer a defense for what has happened?

John Chrysostom explains to Basil that his deceit was actually for the benefit of Basil. John Chrysostom seems to be saying that while there actually was a deceit involved, his intentions were in reality, good. In other words the end justifies the means.

Book II

Book II begins with a restatement of John Chrysostom’s explanation (perhaps his rationalization). “that it is possible to make use of a deceit for a good purpose, or rather that in such a case it ought not to be called a deceit, but a kind of good management worthy of all admiration, might be proved at greater length; but since what has been already said suffices for demonstration, it would be irksome and tedious to lengthen out my discourse upon the subject.”

John evidently feels that he has made his case.

Basil now asks “what advantage have I derived from this so called good management”?

John Chrysostom sets forth his argument. In the Gospel what did Jesus ask of Peter to prove his love for him? The answer was that Peter should feed his sheep. If Basil truly loves the Lord, what greater proof could he have than by feeding the Lord’s sheep and caring for his flock as a priest. The Lord did not ask Peter to fast and keep vigils, he asked him to tend his sheep. Should not Basil regard his ordination, even though it was through deception, as a blessing?

This task is go great; John Chrysostom reminds him that most men and all women have been excluded from the task.

The shepherd who cares for the animals must contend with the wolves and the robbers, but the shepherd who cares for Christ’s flock will be engaged in a very great warfare. He must contend with principalities and powers. The priest must be aware that he is in a warfare. He must be aware that he is in greater danger from the adversaries than the man who cares for animals. If the shepherd who cares for animals runs away, no one will follow him. His enemies are only interested in the sheep. But if the priest runs away, the adversary will follow him to overthrow him.

The pastoral office is far more difficult than that of the shepherd. The shepherd can control the sheep by keeping them in the sheepfold. The priest cannot do that. And if the human physician has difficulty diagnosing the cause of human illness, how much greater is the task of the priest to discern the diseases of the character.

The priest cannot forcibly correct the failings of his flock. It is only when they submit willingly can he do anything. And when the priest deals with the faults of his people, he must not apply punishment according to the seriousness of the fault, but rather according to the disposition of the sinner. The priest must exercise great discretion as he works with individual people. He has to have a myriad of eyes seeing all things. No sinner can be dragged back to repentance. The priest must not despair of his people, but hope that God’s grace will change them.

The priesthood is a very difficult ministry. Zeal for the flock is surely testimony to the priest’s love for Christ. At the point Basil raises the obvious question. ‘Well John, do you love the Lord?’ John Chrysostom responds, “Yes, I love the Lord, but I fear of provoking him”. Basil responds that John Chrysostom is talking in riddles. How can he say that he loves the Lord but say that out of his love for the Lord, he refuses to care for the Lord’s flock.

John Chrysostom’s response –should we say excuse– is brief and to the point. I am not qualified. “The infirmity of my spirit renders me useless for this ministry.” Basil responds “you speak in jest.” If the burdens of this office were so great as you say, why didn’t you rescue me? Sorry John Chrysostom, you were only acting in your own interest. I am not that wonderful and distinguished person you make me to be.

John Chrysostom’s response is that in reality he knows Basil even better than his parents. Every man who is recommended to the priesthood should be examined carefully by some who truly knows him. Consequently John Chrysostom cannot be condemned for being party to Basil’s ordination. John Chrysostom sees himself as blameless. Basil insists that he is not worthy. John Chrysostom responds that Basil is a man of great charity which is the most important of all virtues. John Chrysostom reminds Basil of how Basil was even willing to lay down his life for one of their friends who had been falsely accused. John Chrysostom is a trained lawyer. His case is strong. Basil blushes scarlet. John Chrysostom defends his own running away by saying that he had not intention of insulting those who wanted him to be ordained. In reality, he probably had saved them from blame.

Book III

As Book III opens John Chrysostom continues to defend himself “I was not puffed up by arrogance of any kind. They must not think that I would have disdain for the office of priest. It exceeds a kingdom as much as the spirit differs from the flesh. If anyone should think that John Chrysostom somehow despised the office of the priesthood, the person who held that opinion really does not understand the dignity of the priesthood. John Chrysostom insists that if it were glory that he wanted, he should have gladly accepted ordination rather than run from it.

“For the priestly office is indeed discharged on earth, but it ranks among the heavenly ordinances for the Paraclete himself instituted this vocation. While yet on earth the priest has the ministry of angels. The consecrated priest should be as pure as if he were standing in heaven amidst the angelic powers. Here John Chrysostom speaks of the liturgical life of the priest and the sublime privilege enjoyed by the earthly priest.

“But if anyone should examine the things that belong to the dispensation of grace, he will find that, small as they are, yet are they fearful and full of awe.” “For when thou seest the Lord sacrificed, and laid upon the altar, and the priest standing and praying over the victim, and all the worshippers empurpled with that precious blood, canst thou then think that art still amongst men, and standing upon earth? Art thou not, on the contrary, straightway translated to Heaven, and casting out every carnal thought of the soul, does thou not with disembodied spirit and pure reason contemplate the things which are in Heaven? Oh! What a marvel! What love of God to man! He who sitteth on high with the Father is at that hour held in the hands of all, and gives Himself to those who are willing to embrace and grasp Him. And this all do through the eyes of faith! Do these things seem to you fit to be despised, or such as to make it possible for any one to be uplifted against them?”

Elijah only called down fire from heaven. The priest calls down the Holy Spirit. Who can despise this great mystery unless he is mad. What great honor has the Holy Spirit given to the office of the priest. They celebrate these great mysteries. What the priest does here on earth, God ratifies above. It is through the hands of the priest that man is regenerated through water and the Holy Spirit.

If one considers the awesomeness of this ministry, “will anyone” John Chrysostom asks, “venture to condemn me for arrogance?” Instead of condemning the man who runs away from this responsibility, John Chrysostom’s critics should be condemning those who come forward eagerly seeking this dignity for themselves. “I know” he says “the magnitude of this ministry and the great difficulty of the work; for more stormy billows vex the soul of the priest than the gales which disturb sea.”

Having pointed out the magnitude of the priestly ministry, St. John goes into detail regarding the difficulties of the ministry. He uses the image of a storm and the call the sirens in Greek mythology. On the rock of the sirens there are wild beasts set out to destroy the priest. The beasts are the vices both within the priest himself and vices from others around him.

Here in this metaphor he examines the issues that face each priest. Hearing them, it is obvious how well he understood his subject and how, after 16 centuries how little has changed.

Speaking of the stormy billows that vex the soul of the priest, John Chrysostom says that the “first of all is that most terrible rock of vainglory (or in modern English, excessive pride), more dangerous than that of the Sirens, of which the fable mongers tell such marvelous tales. for they were able to sail past that and escape unscathed; but this is to me so dangerous that even now, when no necessity of any kind impels me into that abyss, I am unable to keep clear of the snare:

But if any one were to commit this charge to me, it would be all the same if he tied my hands behind my back, and delivered me to the wild beasts dwelling on that rock to rend me in pieces day by day. Do you ask what those wild beasts are? They are wrath, anger, despondency (giving up all hope) (a conviction of uselessness, further effort) (he will come back to these again) envy, strife, slanders, accusations, falsehood, hypocrisy, intrigues,(church politics) anger against those who have done no harm,(“kicking the dog” syndrome, i.e. taking one’s anger out on innocent people like members of our family) pleasure at the indecorous acts of fellow priests, sorrow at their prosperity, love of praise, desire of honor (which indeed most of all drives the human soul headlong to perdition), doctrines devised to please, servile flatteries, ignoble fawning, contempt of the poor, paying court to the rich, senseless and mischievous honors, favors attended with danger both to those who offer and those who accept them, sordid fear suited to only the basest of slaves, the abolition of plain speaking, a great affectation of humility, but banishment of truth, the suppression of convictions and reproofs, or rather the excessive use of them against the poor, while against those who are invested with power no one dare open his lips. For these are the wild beasts…. of which I have spoken.”

But the priesthood itself is not the cause of all these problems but it is we who defile it.

The priesthood is sometimes offered to those who do not know their own soul, who do not know the gravity of the office, and who are blinded by inexperience.

John Chrysostom is especially troubled by how prelates were chosen in his time. They were not chosen from among the best men.

There is one quality that a priest must have that is very important. He must not lust after the office. Sometimes even those who have a natural inclination for the office, once they have it are taken over by his weaknesses. It is perfectly fine to want to do the work of the office of the bishop, but some seek not the work but only the authority and power. The priest must be of sober mind, and a man of character.

The life of the priest or bishop is actually much harder than the life of the monastic. To be indifferent to food and drink, and a soft bed is for many no hard task. Some have been raised this way from their youth. But another matter is what the bishop and priest have to endure. Insult and abuse, coarse language, gibes from inferiors….this is what few can bear. Sometimes men who have been able to endure the asceticism’s he mentioned are totally unable to endure the abuse from people. These men sometimes are filled with rage and anger causing disaster to themselves and to the people. It is one thing for a prelate not to fast or to go barefoot….no harm would come to the church, but a furious temper can be disastrous. Wrath is a most destructive thing in the life of the church. “Nothing clouds the purity of reason, and….the mental vision so much as undisciplined wrath.”

People look to their priest to be a model of behavior. “it is” he says “impossible for the defects of priests to be concealed, even trifling ones become speedily manifest.”!!!!

Given the very great responsibilities of the office and the accompanying temptations, why, John Chrysostom asks would you want me to come near this pyre!!!

And among all the dangers and vices, few are as problematic as envy.

John Chrysostom says, “as the tyrant fears his body guards, so also does the priest dread most of all his neighbors and his fellow ministers.” “For no others covet his dignity so much, or know his affairs so well as these; and if anything occurs, being near at hand, they perceive it before others, and even if they slander him, (they) can easily command belief, and by magnifying trifles, take their victim captive.” In the cases of his fellow ministers, the meaning of scripture is actually reversed “when one member suffers, all the members suffer, and when one member is honored, all the members rejoice”. (I think John Chrysostom is saying that in the case of priests when one member suffers the rest rejoice. And when one is honored the others suffer.)

Do you, John Chrysostom asks, want to send me into this kind of warfare?

“Would you like me to show you yet another phase of this strife, charged with innumerable dangers?” “Take a peep” he says at the public festivals when it is generally the custom for elections to be made to ecclesiastical dignities.” The whole thing turns into a circus. Parties bicker with one another. They argue that a certain man should become bishop because he comes from a certain family, or because he is well to do and we won’t have to support him, or because we happen to be his good friends, or because we are related to him.

One is too old and another too young. What about the real qualifications of the man? John Chrysostom says that he used to be critical of how secular rulers were chosen, but now seeing the same thing in the life of the church he finds himself less critical. So much is done out of envy.

One would think, John Chrysostom suggests that great piety would seem to qualify a man for the priesthood, but he knows, he says, many men who were true ascetics, but when they entered the ministry and were called to correct the errors of others, they proved disastrous.

But once a man has become a bishop, then he is really in for a difficult time. He must be dignified, but free from arrogance. Formidable but kind. Apt to command, but sociable. Impartial, but courteous. Humble but not servile. Strong, but gentile.

John Chrysostom then brings up three areas of ministry that he finds especially troubling. The care of the widows, the care of the virgins, and the “judicial functions”, that the bishop apparently has to occasionally carry out. The bishop has charge of what seems to be the “charity fund” of the church. Out of these resources he has to take care of the women who are in the group of widows. Many it seems are classified as widows who do not lead exemplary lives. And if a father worries about one daughter that she may eventually have a happy marriage and family, the bishop has to worry about his many consecrated religious.

And it seems that no matter how hard he may try to carry out the various ministries, he is going to be criticized. “If a bishop does not pay a round of visits every day, more even than the idle men about town, unspeakable offense ensues. (Father doesn’t visit the people.) “For not only the sick, but the whole desire to be looked after, not that piety prompts them to this, but in most cases they pretend claims to honor and distinction. And if he should ever happen to visit more constantly one of the richer and more powerful men, under the pressure of some necessity, with a view to the common benefit of the Church, he is immediately stigmatized with a character for fawning and flattery.”

And that is not all. A bishop will be criticized even for the way he speaks to people and looks at people. They have to undergo a scrutiny and to bear a load of reproaches for the way they use their eyes, for the tone of their voice, the look on their face, for the degree of their laughter, and if he is speaking publicly he better look at everybody or somebody will become insulted.

He will find himself often unjustly accused. And when this happens, as it will, he will find himself suffering from two additional problems, namely, wrath, or anger, and depression. John Chrysostom calls it dejection. We call it depression. And I suspect that many priests suffer from depression. Maybe it is something that goes with the job. If a man is unjustly accused, it is “utterly impossible” to avoid anger.

And if a bishop has to cut someone off from communion from the church, how careful must he be to keep the person from even a worse life.

And so John Chrysostom concludes by saying “I did not make this escape under the influence of pride or vainglory, but merely for my own safety, and consideration for the gravity of the office.”

Book 4

In Book 4 John Chrysostom takes up the importance of the teaching and preaching office of the priest or bishop. The priest or bishop is engaged in a battle and he must be prepared for that battle. Consequently, the Word of Christ must richly dwell in him. His adversary is the devil. But the priest must know how to respond to the Greeks, to the Jews and to the Manichaean’s and the Gnostics. The priest must know how to interpret the Old Testament, neither rejecting it like the Gnostics nor revere it to the extent that the Jews do. He must be able to answer the Sabellians and the Arians. He must know the way of Orthodoxy. The priest or bishop has to be a student of scripture and theology.

He must be one who reads the scriptures. As St. Paul instructed Timothy “give heed to reading, to exhorting, to teaching…. for in doing this thou shalt save both thyself and them that hear thee”. To be honored are those presbyters who labor in the Word and in teaching.

To carry out this ministry he has to be skilled in speech. The priest must do all in his power to gain this means of strength. Here St. John makes an important clarification for his friend Basil. He is not talking about great oratory. The priest is not asked to be a Demosthenes or Plato. “I pass by all such matters and the elaborate ornaments of profane oratory; and I take no account of style or delivery; let man’s diction be poor and his composition simple and unadorned, but lethim not be unskilled in the knowledge and accurate statement of doctrine…” Paul himself was known not for his miracles but for his words.

In the defense of the faith, the priest must be skillful in disputation lest his people fall into heresy.

Book 5

In Book 5 Chrysostom continues with the importance of the ministry of preaching and teaching. “How great is the skill required for the teacher in contending earnestly for the truth, has been sufficiently set forth by us.” But there is something else. “The expenditure of great labor upon the preparation of discourses to be delivered in public.” Here the greatest of preachers tells us that we have to prepare our sermons. The people who come to hear the priest probably have not come to learn something. It is more likely that they “assume instead the attitude of those who sit and look on at the public games….” And if you happen to quote some other authority in your sermon, you will be regarded as a thief “For the public” he says, “are accustomed to listen not for profit, but for pleasure, sitting like critics of tragedies and musical entertainments…” The preacher must have two important characteristics…he must have the ability to preach well, but he must be completely indifferent to praise. If either of these be lacking, the remaining one becomes useless. (Chrysostom had far more hostile audiences than priests of our era.)

The bishop must be strong in both of these points. In addition to being immune to praise, the bishop also must be indifferent to two other vices…..slander and envy. If the bishop be slandered by what St. John calls the “common herd”, he should try to extinguish it immediately.

A priest must be as a father to his family. As a father is not bothered by the insults or blows of his very young children, so too should the priest not be disturbed by censures of the people. And don’t get too used to praise, it can become addictive.

Sometimes there are priests who have great ability in preaching. These he says must actually toil the more when they preach. “Since preaching does not come by nature, but by study, suppose a man was to reach a high standard of it, this will then forsake him if he does not cultivate his power by constant application and exercise. So that there is greater labor for the wiser than for the unlearned.”

The preacher should judge his own sermons and not worry about what other people say about them. Public fame for a preacher can become like beast that the preacher will have a very difficult time in defeating. (Story of the preacher and the lay brother.)

John then says “why need I detail the rest of these difficulties, which no one will be able to describe, or to learn unless he has had actual experience of them.”

Book 6

St. John then brings up the fact that the priest is a man accountable. If we do not care for those who are entrusted to us, our penalty is not simply a matter of being ashamed of ourselves. An everlasting chastisement is waiting for such shepherds. If a millstone awaits the one who causes just one to stumble, then what of the pastor who causes many to fall?

And if it is difficult to be a recluse with all their protection, how much harder is it to be a priest dealing with people in the world. This office needs the virtues of an angel. He has need of far greater purity than other men.

And if all these troubles were not enough, women too, he says can be a temptation. “For beauty of face, elegance of movement, affected gait and the lisping voice, penciled eyebrows and enameled cheeks, elaborate braiding and dyeing of hair, costliness of dress, variety of golden ornaments, and the glory of precious stones, the scent of perfumes, and all those matters to which womankind devote themselves are enough to disorder the mind, unless it happen to be hardened against them, through much austerity of self restraint.” (He did not miss much).

But sometimes it is not just the beautiful who are a temptation. Sometimes the devil can tempt us with a very plain woman for whom we might feel pity for her poverty or condition of life.

And if we think that our relations with people are a cause of concern, of greater concern is the relationship between the priest and God. Consider he says what manner of hands they ought to be which minister in these things? When the priest stands at the altar he is surrounded by angels. Chrysostom then narrates a story of one priest who saw the heavenly host in his sanctuary. The soul of the priest must shine like a beaming light over the whole world.

John now finds Basil weeping before him. And so he asks him why are you weeping. “For my ease (that is John’s ease in having escaped ordination) does not call for wailing but for joy…”

Basil replies:

“But not in my case, this calls for countless lamentations. For I am hardly able to understand to what degree of evil thou hast brought me. For I came to thee wanting to learn what excuse I should make to those who find fault with thee; but thou sendest me back after putting another case in the place of that (which) I had. For I am no longer concerned about the excuses I shall give them on thy behalf, but what excuse I shall make to God for myself for my own faults. But I beseech thee, if there by any consolation in Christ, if any comfort of love.., and mercies, for thou knowest that thyself above all hast brought me into this danger, stretch forth thine hand, both saying and doing what is able to restore me, do not have the heart to leave me for the briefest moment, but now rather than before let me pass my life with thee.”

Chrysostom concludes the treatise with his answer to Basil.

“But I smiled, and said, how shall I be able to help, how to profit thee under so great a burden of office? But since this is pleasant to thee, take courage dear soul, for at any time at which it is possible for thee to have leisure amid thine own cares, I will come and comfort thee, and nothing shall be wanting to of what is in my power. (thanks a lot)

On this, he weeping yet more rose up. But I, having embraced him and kissed his head, led him

forth, exhorting him to bear his lot bravely. For I believe, said I, that through Christ who has

called thee, and set thee over his own sheep, thou wilt obtain such assurance from this ministry as to receive me also, If I am in danger at the last day, into thine everlasting tabernacle.”