Word Magazine February 1966 Page 8-9

EASTERN ORTHODOX

VERY REV. ALEXANDER SCHMEMANN

The National Broadcasting Company presents FAITH IN ACTION, a program designed to bring the viewpoints of those of many beliefs. In the first two programs concerned with Eastern Orthodoxy, the Very Reverend Alexander Schmemann, Dean of St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in Crestwood, New York, and author of “The Historical Road of Eastern Orthodoxy,” delivered the following talk:

PART I.

The Western Man, and in particular the Western Christian, doesn’t know much about the world of Eastern Orthodoxy, that is, the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The final separation between the East and West took place in the 11th century, in 1054; and since then the Western history was so rich in events, so complex and tragical, that not many people in the West kept the memory of the great Eastern Church which at the same time was going through its very dark period.

Therefore, it’s good if we begin by certain historical facts, by a general historical presentation.

It is certainly not an accident that the world into which the Church entered after it left its Jewish childhood in Palestine was called the Greek-Roman world; not only Greek, not only Roman, but Greek-Roman. It was a world in which that synthesis between the Latin West and the Greek East was already accomplished within one culture, which we call usually Hellenistic culture. It is within this world that Christianity developed at first when it had its formative age. And there can be no doubt—I think all historians will agree—that in this formative age it was the Eastern part of the Christian world, usually known as the Byzantine world, that had the leading role. It was in the East that Christianity took its historical form, acquired its shape, its canon, as a theologian would say.

And I think the best way to present this canon or shape of historical Christianity is to mention the three main dimensions of the Byzantine Eastern Orthodox Church.

It begins, certainly, with the conversion of the Emperor Constantine in 312, the Roman Emperor who, at the famous battle at Ponte Milveo near Rome, became a Christian. From that moment on, the historical home of the Church was the Roman Empire as it developed primarily in the West when Constantine transferred the capital city of the empire from Rome, first to the city of Nicomedia, and then later on to the newly founded capital of Constantinople.

Constantinople is the center of that Byzantine world, and it was around Constantinople, in Asia Minor, in Syria and in Egypt that those dimensions of Eastern Orthodoxy, which still are shaping and forming it, developed. The first of these dimensions we may call the intellectual.

Eastern Orthodoxy means that the dogma, the doctrinal, the intellectual content of religion is given a very important priority. This theological content was developed not in academic work, but in a series of great theological disputes, controversies, in which basically what happened was the interpretation or the formulation of the content of Christian faith in terms of Greek philosophy. This is the real achievement, the first great intellectual achievement of Eastern Orthodoxy: the kerygma, or sermon, the proclamation of the Gospel given its intellectual consistency within the terminology of Greek mind and Greek thought.

This resulted in those great dogmas of Trinity, Christology, the person of Christ, His Divinity, His Humanity, the Holy Spirit, the Mother of God, and even a doctrine known as the Doctrine of Icons.

Eastern Orthodoxy historically is primarily a body of doctrine which formulates a certain vision of God, man, history, time, et cetera.

But this intellectual vision—I am now coming to the second dimension—-found its true expression in an artistic language, primarily the language of architecture, worship, and liturgy.

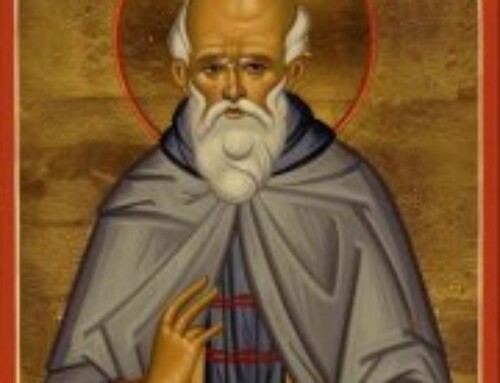

Iconography also should be mentioned here. It was within this great Byzantine Rite, or Byzantine Liturgy, that Orthodoxy found its real heart. And even if today it’s still called the Liturgical Church par excellence, it’s not only because our worship has presented certain colorful archaic forms attractive to Western man, but because it is in worship, in the Doxology, in the glorification of God, that an Orthodox finds the real center, the heart of his religious life.

Now, St. Sophia in Constantinople, the pattern, the prototype of all Orthodox Churches, is more than the place where people worship. It is in itself a vision of the new creation. The great dome covers not only the Church but potentially the whole world. St. Sophia exemplifies the great mysterion, the mystery of the Liturgy in its rich symbolism, and that great hymnography which is being sung in church. All this is not only an art of prayer; it is a manifestation, the revelation, the communication of that ultimate reality which, according to Eastern Orthodoxy, has been revealed to us, communicated to us in Christ and by Christ—the reality which, according to another Orthodox saying, makes the life of the Christian the heavenly life on earth.

This is the second dimension of historical Byzantinism.

And then finally the third dimension, after the intellectual and the liturgical, is that great world of spirituality which developed primarily in the monastic movement. It was in the fourth century after the Roman Empire became Christian that thousands and thousands of men left, if I can say so, the world and went into the desert in order not to betray, not to give up this ideal of absolute perfection which comes from the Gospel—to be perfect, as your Father in Heaven is perfect.

Now, this monasticism which developed in Egypt with St. Anthony and St. Pacomios, then in Palestine, finally in Asia Minor with St. Basil of Cicarene Cappadocia, was not only one of the possible ways of Christian life according to the Orthodox understanding of it, but it was first of all a sort of laboratory where this whole ideal of human existence as communion with God, as appropriation of the grace and slow transfiguration of man, were put into practice.

Now this great monastic or spiritual tradition, therefore, became the real doctrine of man in Eastern Orthodoxy. And this doctrine of man is centered primarily on the idea of mans’ transformation or transfiguration. He is to become the temple of the Holy Spirit. He is to anticipate eternal life in his life here in this world.

Now, the doctrine of that spirituality has been codified more or less in the body of writings known as the Philokalia, the great spiritual writings of the Fathers, the Fathers of the desert, or some of the great teachers of Latin Byzantium.

Thus, we have in Byzantium the foundation of the Eastern Orthodox world. Today there are many Orthodox Churches, many national Orthodox Churches. But they are still a part of this Byzantine synthesis, encompassing a body of doctrine, the dogma of the Church, the doctrine of the seven ecumenical councils and of the Greek Fathers, the Liturgy of the Byzantine Rite, the Liturgy connected with the names of John Chrysostom and Basil the Great. And it is finally the ideal of life that comes to us from men like Isaac of Syria, or Maximus the Confessor, that constitutes still the main inspiration of life.

This is what all Orthodox Churches and what all Orthodox people have in common, their foundation, the source, the Byzantine pattern of Orthodoxy.

Now, all this lasted for many centuries, and yet ended in an historical catastrophe.

In 1453 Constantinople was taken by the Turks, and the Byzantine Empire came to an end. Within the next hundred years all independent Orthodox Churches in Syria, in Egypt, and elsewhere, were under the cloak of Islam, and this brilliant millennium came to an end.

However, this was not the end of Eastern Orthodox history. It continued. Byzantium as an historical reality came to an end. Byzantium as a spiritual reality gave birth to many new developments, and those developments will later on lead us to the 20th century and to cities like New York, Chicago, or San Francisco.

Therefore, in the end of one historical era, the beginning of the dark age of Orthodoxy in fact provoked new developments, new beginnings, and these involve, first of all, the geographical expansion of Orthodoxy, the Byzantine mission. There is the birth, for example, of the great Slavic Christianity, Russian Christianity, et cetera.

Second, there was a new encounter with the West. First, a negative one during the Holy Wars of all kinds which unfortunately provoked a world of great misunderstanding.

And finally came the influence, the progress, the growth of modern Orthodoxy, the Orthodoxy of the Diaspora: the presence of the Orthodox Churches today virtually in every land, in every geographical area of the world.

Thus, summing up, we can say that what began in the Greco-Roman world, what followed its first fullness, its first expression in the world of Byzantium, then went into a sort of dark age, but continues today in new forms and with the same loyalty to its foundation.

ART II.

1453 marks a tragical date in the history of the Eastern Orthodox Church. In that year the city of Constantinople, which for more than a thousand years was the center of the Byzantine Orthodox culture, was taken by the Turks and for many centuries after that the whole Eastern world, the world of Eastern Orthodoxy, rather, which included the flourishing provinces of Asia Minor, Syria and Egypt, ceased to be in the hands of Orthodox rulers.

And yet, it did not stop the growth and the progress of Orthodoxy.

On the one hand, of course, these centuries between the 15th and the 20th were centuries of a great tragedy. Orthodoxy survived, but survived in the climate of constant persecution, A Patriarch of Constantinople died a martyr in the year 1821, killed in his own Patriarchate. And even today what we hear from the See of Orthodox Primacy of Constantinople in Istanbul is always a source of tragedy for all Orthodox hearts in the world.

But, as I said, if this great Byzantine world entered its dark age it gave birth prior to this historical tragedy to new Orthodox Churches. And the first one to be mentioned here in this very glorious missionary development is the birth of the great Slavic Orthodox world.

In the 9th century two Greek brothers by the name of Cyril and Methodius were sent from Constantinople to the Western Slavs, and there translated the whole body of Scripture, Liturgy, and doctrine into the Slavic language.

Their own mission ended rather tragically. They were both expelled from what is today Czechoslovakia, and Latinism triumphed there. But in the translations the whole spirit of that Byzantine mission was picked up, if one can say so, by the other Slavic countries, first by Bulgaria, then by Serbia, and last but not least, at the end of the 10th century, by the young kingdom of Russia, centered in Kiev. And thus began a new chapter in the history of Eastern Orthodoxy which gave not only to the Orthodox world, but one can say to universal culture, great treasures of thought, holiness, and in general, various great examples of what Christian culture is.

At the end of the 10th century the Prince of Kiev, Vladimir, invited bishops and priests from Constantinople and baptized his whole people in the river Dnieper.

From this Christian beginning there developed the great Church of Russia which, in the 19th century, primarily because it was at that time practically the only free Church in a free Orthodox country, gave to the world great theologians, great writers. The names of Dostoyevsky, and closer to us the names like that of Pasternak, for example, whose Doctor Zhivago, which created so much interest a few years ago, showed the depth and the quality and the message of that Orthodox Christian literature of Russia.

If one adds to this the names of many saints produced by the Slavic world again one name may be mentioned here, that of St. Serafim of Zarov, who was canonized only at the beginning of this century, and who yet is a sort of flower grown on the soil of Orthodoxy, reflecting the deep joy of its Liturgy, its spiritual expectation of the kingdom. If one but mentions all this one can see that in 1453 the history of Orthodoxy did not come to an end.

In addition to the great Byzantine tradition, and inside this Byzantine tradition, new material traditions developed. For it belonged to the nature of Orthodoxy to identify itself with the total life of the community in which it lives.

Even today Greeks or Russians do not call themselves Greek or Russian, but simply Christian. And such is the degree of their identification with their faith. And so when one speaks of national Orthodox cultures one touches upon what maybe is the great particularity, the great uniqueness of Orthodoxy. It is this combination of a tradition which is not national in its essence, which is universal dogma, Liturgy, spirituality, and at the same time its complete identification with the soul of the people which it baptizes.

One can really speak as all Orthodox nations spoke of the Holy Greece, the Holy Russia, the Holy Serbia, not meaning moral holiness — for we are quite aware of the many sins and shortcomings of those peoples, individual and social — but of the ideal of national existence. And the ideal of national existence is rooted in the Church, which is not only an agency for prayer or for religious action, but which becomes in a very real sense the central, the pshi, the soul of the nation to which it belongs. Now such was the development of Orthodoxy after the fall of Constantinople.

Little by little the nations which were under Islam were liberated. At the beginning of the 19th century came freedom for Greece. It became a free Orthodox country. Then Bulgaria, then Serbia, then Romania became free.

Then another set of tragedies began. Today a great part of the Orthodox world is again behind the Iron Curtain, and if one limits the analysis of that situation only to Soviet Russia, one can see again how in some 48 years of Soviet atheistic domination in Russia, the great monopoly of the state father could not bring to an end the Church’s existence. The Church reacted, first by thousands of martyrs, of people who went to concentration camps, and then, little by little, by attracting to itself people who could not be poisoned by the atheistic propaganda or by ideologies alien to the Orthodox world.

So all this is the history of achievements and also of tragedies.

But the last thing which must be mentioned in this very brief historical analysis of Eastern Orthodoxy is the new phenomenon, the expansion of Orthodoxy beyond the Christian East.

I began by comparing the Christian East to the Christian West. Orthodoxy is the Eastern form of Christianity, though it has always claimed to have preserved the fullness of faith, to be the true Church, not to be just a geographical expression of Christianity. In fact, its history was an Eastern history.

Yet the tragedy which I mentioned resulted in a great geographical expansion of Orthodoxy: the Greeks expelled from Turkey in the twenties of this century, the Russian refugees, people who were leaving the various non-Orthodox countries of Central Europe.

All these different sources fed what today is the great Orthodox Diaspora.

It is almost a strange feeling when driving through Los Angeles to see an Eastern Orthodox Church all of a sudden. This is the East coming to the West, and again without speaking of what happens in Australia or in South America, where there are Orthodox Churches. If one just limits it to the United States one should say that today Orthodoxy is here not only as a sort of Eastern ghetto, but very quickly develops into a real factor in the American religious and cultural scene.

There are some five to six million Eastern Orthodox in America. There are several thousand parishes in practically every area, and little by little a new generation of Orthodox born in this country, educated within the American culture, yet faithful to this whole Byzantine and Orthodox heritage, doctrine, Liturgy and spirituality, are making their entrance not only as refugees, not only as those who remember the past, but who want to make Orthodoxy a real part, if not the moving force, of their life and existence in the West.

We are living through this chapter now and therefore it doesn’t belong yet to history, but there can be no doubt that the critical moment is behind. This transition from what .American sociology knows as the immigrants’ Church to the native Church is on its way, and although of course it provokes many difficulties, many misunderstandings between generations, between

various groups, et cetera, the last events, the creation of a Standing Conference of Orthodox Bishops uniting all the Orthodox traditions into one, the practical cooperation, the Pan-Orthodox Schools and Seminaries: all of these things show that we are on our way, the way which before us the Lutherans and the Catholics knew to become not simply one of the American groups, but to make the presence of Orthodoxy felt in the shaping which never ends, the shaping of this great country.

Certainly there’s a great hope that this integration of Orthodoxy into America is something which will mean much, not only for Orthodoxy, for those Orthodox who are here, but for Orthodoxy universal, and also, one may hope, for the West itself.