What do Icons Mean?

What do Icons Mean?

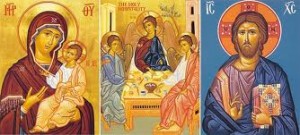

The very meaning of the icon has as its foundation the incarnation of Our Lord Jesus Christ. “And the word was made flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). Christ is “the icon of the invisible God” (Col.1:15), and the transfiguration on the mount offers support of this (Matt. 17:1-13). It is because Christ became man and allowed man to glimpse on the divine glory of Heaven that we are able to write icons and venerate images of Christ, the Theotokos and the Saints. If Christ had not become incarnate, and had not revealed to us his transfigured glory on the mount, it would be impossible to depict the spiritual realm of Heaven in icons. Precisely because of the incarnation and transfiguration, everything in the icon is represented in relation to Divinity. As you will see this impacts all parts of the icon, from how the face is painted, to the robes, to even the “scenery” of the festal icons. While the incarnation is the basis of iconography, the icon itself in its role as a window into heaven, affirms the incarnation and speaks of God’s great mysteries. The chief task of the icon is to proclaim the wonder and mystery of Christ, the Theotokos and the saints, and yet at the same time, to remind us they were human like we are, and to call us to the same spiritual perfection which Christ’s incarnation allows us to seek. All naturalism, whether it is spacial, figural or proportional, is set aside and man, landscape and architecture are shown in a transfigured state.

One of the first things which I discovered about icons before converting to Orthodoxy is that icons are initially not easy to see. At first they appear distorted and unreal, almost impressionist or surreal, full of symbolism. In our society with its western art, we are very concerned with what something immediately says to our external, empirical senses. Society’s concern is with beautiful people, homes and cars, and it is not concerned that often under all this “beauty” lies death and internal corruption. Contrary to the way our society sees things, the icon is not meant to excite our external senses. It is not painted to depict the mundane everyday life, but rather the spiritual realm. It is written as a “window into Heaven,” a physical means which allows us to gaze into the invisible spiritual reality. The simplicity of the icon is not meant to stir your emotions but rather to quietly invite you to leave the world for a moment and guide every emotion toward the contemplation of the Divine. To Achieve this level of spiritual communion, one must quietly, prayerfully and patiently gaze on the image. It is the way to prayer, and the means of prayer itself.

The communion which the icon calls us to is achieved through a symbolic language which the icon uses. In order to convey this symbolic language the clothing styles, colors, gestures, architecture and human form in the icon are fixed. The painting of iconography must not be based on artistic speculation, emotion or abstract ideas because the icon depicts the mystery of Heaven. Rather, it is based soundly in the teachings of the Orthodox Church. To depict these teachings requires much study, meditation and attention to details, as well as artistic skill and an understanding of Orthodoxy. The iconographer must understand what parts of the icon he can adjust using his best artistic skills and what parts of the icon he ought to leave intact. How can someone who has no knowledge of Orthodoxy depict what is inherently Orthodox? The style of iconography is not meant to hold the painters of icons hostage to one particular style of painting, but rather to liberate them and allow for the continual painting of orthodox icons and defend against theological and iconographic heterodoxy. It is also there to liberate Orthodox Christians. One of the beautiful things about iconography is that an Orthodox Christian upon seeing an icon of Christ, the Theotokus, any of the more popular saints or a feast can instantly recognize the icon as such. This is not the case in western art. The way western artists have depicted the Theotokos, for example, has changed with each period of art and with each artist. Michael Quenots book “The Icon, Window on the Kingdom” has a wonderful illustration which depicts just this.

In order to allow for this language of iconography to be understood, certain meanings are ascribed to the subjects of the icon. People of importance in icons are often depicted as larger than other people in the icon and are always indicated by name on the icon. In icons of single saints, the saint is also ususally depicted with the instrument of his or her salvation. Bishops are usually depicted wearing episcopal robes, whether monastic or liturgical, holding the gospel and giving a blessing. The blessing hand is formed in the monogram of the name of Christ, ICXC, just as an Orthodox Priest blesses. The evangelists are depicted holding the gospel, St. Paul the epistles, and great spiritual writers a scroll with one of their more noted writings. Martyrs are depicted holding the crown of martyrdom, the cross or the instrument of their martyrdom. St. Andrei Rublev, the great Russian iconographer of the fifteenth century, is depicted holding the icon of the Trinity which he painted, and which the Russian church sees as the standard for all other icons. The subject in the icon is usually depicted looking straight at you, or at a 3/4 angle. Only when the person depicted in the icon has not yet achieved the spiritual perfection of Heaven are they depicted in a profile. Icons gaze into eternity, and yet while focused on the divinity, the transfigured icon is not avoiding the earthly realm but rather gently addressing it and calling it to be transfigured in Christ as well.

The physical features of the icon are also very important in conveying this symbolic spiritual language. The subject of the icon is a person transfigured by the love of Christ and thus the light of the icon is interior, not exterior as in other forms of art. Because of this the areas of the robes and skin which stick out the most have the brightest highlights. The forehead on many icons is often high and convex, to express the power of the spirit and wisdom. Ascetics, monks and bishops are given deep wrinkles in their cheeks. The nose of the icon is long and thin, which gives it a sense of gracefulness, it no longer smells the odors of the world, but rather the sweet incense of Heaven. The lips of the icon are closed expressing true contemplation, which requires total silence. The eyes are large and pronounced, gazing into Heaven. While the physical features of the face are spiritualized, they still retain a likeness to the saint depicted. Thus the face of St. Peter is different from that of his brother Andrew and from that of St. Paul. The hands are either holding the instrument of the depicted saint’s salvation, raised in a work of mercy, or giving a blessing. The blessing hand, when depicted, always blesses with the fingers formed in the monogram of the name of Christ, ICXC, the way an Orthodox priest blesses. The feet, if depicted, walk in the way of God. The halo symbolizes the Divine light which radiates from the person who lives in close communion with God.

As important as the physical features of the icon are the colors which are used to depict the subject. Before I go on to discuss the meanings which are often associated with the colors in iconography, I must first address the use of color itself. Many people think the colors of the icon have some deep theological meaning to them, and that they must be set in stone. This may or may not be the case, depending on which iconographer you speak to. There are definite psychological meanings which colors have, and there are certain colors which are generally used to depict certain ideas in icons. However, iconography while being a sacred art, is still art. The fathers of the Church were traditionalists, however, they were not stagnant traditionalists. Iconographers in the past have painted certain icons in certain colors because it was theologically correct to do so as well as visually appealing. The iconographers job is to depict an icon which is both theologically correct and in good artistic taste and visually pleasing, and the necessity of good artistic taste often has a role to play in what colors are used in the icon. I recently began painting an icon of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus which is an icon of seven young soldiers sleeping next to each other in a cave. In painting this icon it was necessary to plan out the colors of the robes of the soldiers in order to make sure there was artistic harmony and balance to the icon. It would have been visually unpleasing to have two of the soldiers in one corner of the icon wearing red and to have no red anywhere else on the soldiers robes. This artistic harmony, for lack of a better phrase, is as important to the icon as the theological orthodoxy of the icon. A visually unpleasing icon can be as disturbing as a theologically incorrect one because it draws attention to what should not be important, namely the skills of the iconographer, and draws attention away from what is most important, namely the message which the icon is there to convey.

Having said this about icon colors and artistic harmony let us now discuss the meanings commonly associated to colors. Gold is used to depict divinity as it is a rare and precious metal, when light strikes gold it gives a radiance which most closely reflects uncreated light. Gold leaf, or a golden color of paint is used for the halo. White, like gold, is used to depict uncreated light, as well as physical and spiritual purity. Christ’s robes at the transfiguration and from the resurrection on are painted white, or sometimes gold. The color blue is used to depict transcendence, truth and humility. A famous icon of St. Ignatius of Antioch depicts the saint wearing a deep blue robe with a blue background. The color serves to remind us of the great spiritual truths which St. Ignatius taught us. Red is the color of blood, martyrdom, youth and beauty, but also the color of sin and war. Martyrs are often depicted wearing red, or as the case with the famous Russian icon of St. George with a deep red background. In one icon the Prophet Elijah is depicted wearing a red robe with a red background because he was taken up to Heaven in a chariot of fire. Christ’s outer garments are blue and his under garments are red to symbolize that he is divine while being filled with humanity. The Theotokos’ outer garments are red, or a deep earthen tone, while her under garments are blue to symbolize that she is human while filled with divinity. Green is the color of the plant world and thus is used to denote spring time and revival. The first icon which I painted was the Angel Gabriel, who is depicted with a green robe, as he was the bearer of the message of the incarnation to Mary. The meaning of the color brown in icons can only be attained in connection with the rest of the icon. The rocks and buildings themselves have no meaning, but only have meaning in the larger context of the icon. Finally, black is the color of death, and the renunciation of earthly values. In the icon of the Last Judgement the damned are painted black as they have lost all hope of salvation. On the icon of the Cross, the cave under the cross is black which denotes death and despair, as are the caves on icons such as those of St. George and the Prophet Elijah. Monks are depicted wearing black robes as the black symbolizes the monk’s renunciation of all that is vain.

The “scenery” in the icon has its meaning in the larger context of the icon as well. Architecture and landscape serve only to tie the icon to a specific event in time. I recently painted for my wife an icon of the Wedding Feast at Cana for our wedding. The feast took place in doors, but in the icon it is shown with the building in the background. This is enough to convey to the viewer of the icon that the feast took place indoors. The icon of the Baptism of Russia has churches and buildings in the background, as well as physical scenery and many faithful depicted in order to convey the historical idea of where and when the event occurred. With the icon of Elijah in the dessert, it is enough to have Elijah sitting in front of a cave to convey the idea of Elijah’s presence in the cave. The same is true with the Nativity icon, and with the cave where the serpent is in the icon of St. George. The mountains and buildings in an icon such as that of St. George are there to give context.

The iconography of our Orthodox Church, with all of it’s symbolism and spiritual meaning, is central to the Church’s teaching. People are greatly influenced by what they contemplate, and so the Church in its love for its faithful has given us iconography in order to help us contemplate God. As a teaching tool, the Church has elevated iconography to the same level as the scriptures and the cross. What the Gospels proclaim with words, the icon proclaims visually. That our churches are full of icons is no coincidence, no fluke of artistic taste. The iconostasis is not there to just look pretty, but rather it plays a dual role. While the iconostasis does function to separate the altar from the faithful and the rest of the church, at the same time it acts as a bridge between the faithful and the eternal heaven. The saints and angels depicted on the iconostasis are there to remind us that we are not praying alone and in vain, but that we are surrounded by the saints and the heavenly host at every liturgy. They also call us to a deeper love and commitment to God. They instruct us in our faith and remind us that we are not the first to walk the sometimes hard, sometimes lonely road of faith. Icons are not only present to the faithful every Sunday at Divine Liturgy but they are also given as gifts to the faithful at very important times in their lives. When I was chrismated a few years ago, Fr. Basil Stoyka gave me two icons, one of Christ and one of the Theotokos. Icons are also given at weddings, for a person’s feast day and an icon of the cross is placed in the tomb with the faithful when he/she leaves this world. In these ways the icon plays an integral role in the lives of the faithful.

The spiritual language which the icon speaks can best be depicted only by a practicing Orthodox Christian. The ancient rules of iconography suggest that an iconographer needs to work at praying while working at painting the icon. Removing the icon from prayer, the icon becomes a mere work of Byzantine style art. There are those who are not Orthodox who attempt to paint icons with no intentions at all of ever becoming Orthodox. Some of their “icons” are technically quite good but when you take a deeper look at them they are missing something. What they are missing is the knowledge, experience and love of Orthodoxy the practicing Orthodox Christian will have. A non-Orthodox Christian who begins to authentically study iconography, it’s language and spirituality will be drawn to Orthodoxy. They will learn of the Orthodox Church’s teachings through the painting of the icon, will learn of it’s rich and abundant history and tradition, will learn it’s spirituality while praying with the icons and will experience the Heavenly beauty of the Divine Liturgy while having their icons blessed. If they are open to the work of God they will become Orthodox or they will merely remain a painter who depicts something which he can not understand. This is inevitable for icons are inherently Orthodox.

Having discussed this language of iconography we see that everything in the icon points to the incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ. In the past four years of painting icons, studying them and praying before them I’ve come to the personal revelation that it is indeed the contemplation of the Divine which is the goal of the icon painter as well as that of the faithful praying in front of the icon. I have painted many icons, prayed before many more, and in doing so have been brought to a much deeper love of Christ while at the same time my humble talents were being used to manifest the incarnation. And yet, I am not the first to come to this conclusion. The Orthodox Church, in its sincere love for its faithful has for centuries pointed this very fact out. To man, God is a mystery, and the Church in its wisdom and love for man has given us the icon to help us gain a glimpse of Heaven.

Michael Goltz

copyright Michael Goltz, 2011.