Reprinted from THE WORD, February, 1991, pp. 13-14.

GRACE

by V. Rev. Joseph Allen

We hear the word all the time: Grace. We hear the priest preach about it, speak about it, pray for it. Indeed, we hear it during the Liturgy, immediately before the Consecration: “The Grace of Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Love of God the Father, and the Communion of the Holy Spirit, be with you all.” These are words taken directly from St. Paul (II Cor.13:14) and incorporated into this portion (The Anaphora — the “lifting up”) of the Liturgy.

Now, some of us, when we hear that liturgical line, do not seem to have difficulty in understanding what “love” is, nor what “communion” is — but “grace”? How are we to understand it?

We can begin to understand grace only in opposition to another word, “sin.” In one short line, the Great Apostle Paul demonstrated this opposition: “Where sin abounded, grace abounded much more”, (Romans 5:20).

If sin means an immoral act, the result of that act is “separation”: separation from the brother, separation from oneself, separation from God. We know that we are constantly estranging ourselves from something to which we belong, from someplace toward which we should be moving, from someone with whom we should be united. Our lives are “fragmented”; there is an interior brokeness which longs for completion in the person of the beloved one. The human being yearns to be “completed; ‘ and will not rest until that communion with the “other,” God and our brother, is realized. Thus St. Augustine cries: “My heart is restless until it rests in thee, O God!” In short, sin is both an act and a state in which we know that we are “not at home,” not where we belong, outside the communion which identifies us as His people — and our conscience will not let us rest! Ultimately, we are “at home,” that is, we are where we are “most ourselves;” when we are in communion with God and each other.

We learn from scripture that this condition of separation existed before Jesus Christ was born “in the flesh.” Before that, we were “strangers;” “as sheep gone astray,” “lost and wandering in foreign places.” There was a “wall of partition” between us and God, but “he is our peace, who has made both (God and man) one, who has broken down the middle wall of partition between us,” (Eph. 2:14). This speaks to the entire human predicament, from the man who loves God, to the boy who loves his father, to the woman who loves a man.

Oh, there was the Mosaic Law, and that was good and important, because it taught and reminded the people of God that there was someone on the other side of the wall, something toward which they were struggling. But that law was not the end. Rather, it was but the “schoolmaster;” the teacher, and as St. Paul writes to the Galatians: “Wherefore the law was our schoolmaster, to bring us unto the Christ, that we might be justified by faith.” Then he quickly adds, “But after that faith, we are no longer under a schoolmaster,” (Galatians 3:24-25). Indeed, we are no longer under a schoolmaster, under the law, and there is no need for an intermediator, because with Christ we have a direct access to God; there is no more wall, it has been smashed down by Christ. And now we have been taught the way of love and union (communion) with God and each other.

The ultimate act of grace is when this union happens, despite the fact that we did not, nor do not, deserve it. According to this teaching of grace, the God of the Christians is not a God of the “therefore,” but a God of the “nevertheless!” By this we mean that in grace, something is overcome; grace occurs “in spite of” something; grace occurs despite our unworthiness to receive it. In the end, grace is the acceptance of that which rightly should be rejected!

At the last extent, the ultimate potential for separation, death itself must be dealt with. Does grace find its limitation with death? Indeed, not at all, for even death itself (called in scripture the “last enemy,” the last sin) has been overcome by the grace of God.

In St. John’s Gospel, Our Lord says, “Verily, verily, I say to you, if anyone keeps my word, he shall never taste death!” (John 8:51). None of us, of course, must think that this means we shall not die in our bodily life: “for the form of this life is passing away” (I Cor. 7:31 and I John 2:17). This is precisely the mistake which the Pharisees made, that is, what they could not understand about the meaning of his words. They say to Jesus: “Now we know that you have a demon. Abraham died, and the prophets died also; and you say, ‘If anyone keeps my word, he shall never taste of death’,” (John 8:52). The Pharisees, in such a response, understand neither death nor grace. To begin with, their grasp of death was merely limited to our earthly life; they did not understand the deeper reaches of death, which means, precisely, “separation from God!” Yes indeed, we are mortal, but after Christ, mortality to this earthly, and bodily life does not mean separation from the life of God: “What is mortal is swallowed up by life!” (II Cor. 5:4).

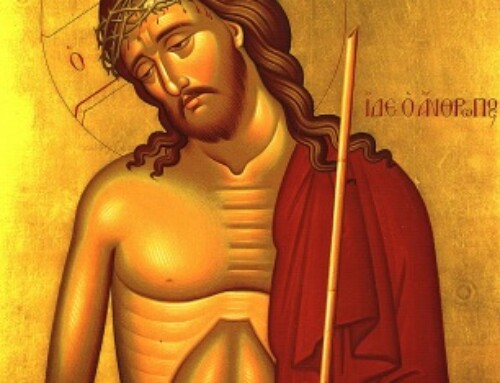

But this union happens only because of grace; death itself is entered, experienced and overcome by God’s grace. (And, of course, the grace of God is fully expressed in Christ.) In the Epistle to the Hebrews, the author says: “But we do see Him who has been made for a while a little lower than the angels, namely, Jesus, for the suffering of death, crowned with glory and honor, that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone,” (Hebrews 2:9).

Jesus “tastes” death for us. It is interesting that the Greek word for “taste” in this verse is genomai, which literally means “to taste and experience” Jesus Christ experiences death on our behalf so that it no longer means separation from life with God; we no longer have that as a penalty, we no longer have to pay that as a wage: “The wages of sin is death, but the grace of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus, Our Lord,” (Romans 6:23).

“Where sin abounded, grace abounded much more.” This is the basis of our very salvation: we did not deserve it, but we received it. Grace abounds: “we are saved by grace through faith ; not of yourself are you saved; it is a free gift of God!” (Ephesians 2:8).

Oh, I forgot — one more thing: if this “free gift” is the basis of God’s relationship to us, that is, that we are accepted even though we do not deserve it, what should be the basis of our relationship to each other?

Father Allen is the Vicar General of the Antiochian Archdiocese and pastor of St. Anthony Church in Bergenfield, NJ. He teaches pastoral theology at St. Vladimir’s Seminary.