Word Magazine September 1999 Page 15-16

FROM CHURCH TO HOME:

SACRED SPACES

By Father Joseph Allen

In many ways the faithful of the Christian East are taught that there is a deep linkage between the Church in which we worship and the home in which we live. This is emphasized when, as the Eucharistic Liturgy nears the final blessing, the Orthodox Priest chants “Let us go forth in peace,” to which the response is, “In the Name of the Lord.” This means that we are to take the peace from the Church’s Liturgy, given “in the Name of the Lord,” into our everyday lives, into our homes. Thus we are called to establish a certain continuity — indeed, an organic linkage —which connects the Church and our home.

One critical way of maintaining that continuity is in how the faithful in the Orthodox East understand sacred space. In short, it is a physical place which speaks to our spiritual life, and this is true in both locations.

But in order to discover the critical importance of sacred space in the life of the faithful, we must explore three areas: the meaning of the sacred and profane, the placing of the sacred marker and the theology of the Icon.

I. Sacred and Profane

How can something “physical” be so important to our “spiritual” life? How is peace “sacred?”

Our understanding begins not with our homes but with the Church itself. Orthodox Christians understand that the Church, i.e., the physical presence, represents a radical break in the space of the profane world. This can be said even if we remember that the Church is really the people, the “people of God.” Relative to the question of space, however, the Church is the sacred “eruption” into the profanity of a fallen world, a world which, left to itself, believes it can simply go on without God. And the truth is that such a world, separated from God, can indeed go on: the bills will get paid, the jobs will get worked, the kids will get clothing, the wars will get fought, etc. In a profane world, devoid of any spiritual presence or longing, these things will indeed get done.

But to the one seeking God’s presence — “where two or three are gathered in my name” (Matthew 18:29) — a sacred place needs to be established. The question is: Why and how is such an establishment needed?

It must first be said that, according to the Gospels, the Church as the primal sacred space does not desert the world, even in its profanity. Rather it is understood to be a “spatial center,” what the religious anthropologists call a “cosmic axis,” one that emits the power of sanctification and order into our lives. As we will see, it is this veritable force which we also need in our lives at home.

But these truths regarding sanctification and order have their roots in the deepest recesses of our minds, as well as in the ancient patterns of our lives. In the earliest ages of humankind, the anthropologists have discovered that the ancients realized the sacred is powerful because it “organizes” and gives form, while the profane is weak because it remains “chaotic” and formless. Without this central point of orientation, the religious man was left in a world in which he could not “measure,” a world which would otherwise remain amorphous, i.e., having no beginning and ending points from which he could order the various facets of his life. We moderns retain much of this in our on-going lives: where one is born, where one studied, where one was married, where one lives, where one dies, etc. These are recurring instances — and there are many more — which hold a sense of spatial sacrality for us; such measures of space are clearly indicative of our primal continuity with the earliest patterns of religious behavior.

If we turn specifically to the Christian East, the Patristic writers who label this “ordered” world in the Greek term, “cosmos,” tie such a meaning to creation itself. They turn to the stories of Genesis: God creates the cosmos by bringing order out of chaos. Thus the heavens and the earth are separated, the land and the sea are separated, the day and the night are separated, and so on. Order is brought about, i.e., out of “the void, the formlessness” (Genesis 1:2). Perhaps the most obvious sign of this “ordered” world, this cosmos, is the manner in which the four rivers run through Paradise, parting the land of Eden into four equal parcels (Genesis 2:l0ff). Such beautiful order marks the perfection of the Paradisiacal creation. The Patristic writers, therefore, understood that such order, which they called “taksis,” is really beauty itself.

This same meaning of God’s creation — that order is beauty — is seen when within the Church the space is ordered and organized by a permanent and enduring pattern of the Icons, the Sanctuary, the Altar, etc. In other words, if Paradise was created into ordered space, so the Church through the same beautiful order is created to reflect that “paradise,” the perfection of God’s original creation. Again, sacred space brings sanctification and order. This, as we will see, is true in both the Church and the home.

II. The Sacred Marker

As stated earlier, when the primitive man wanted to establish order, he created the cosmic axis by placing the sacred stone, or the sacred tree, in the center of his village. This “marker” became a terminal point, a measuring place of origin, and around it he organized his life. But such an object was more than merely a measuring device. He believed them to be hierophanies, sacred revelations, which in themselves contained holiness and sanctity.

While today any monotheist might recognize these as forms of idolatry and paganism, still these phenomena show an ancient longing and yearning in the human soul for spiritual transcendence. For Christians, however, this “form” of yearning is now fulfilled in the final hierophany, the Incarnation of the Theanthropos, Jesus Christ. The forms — the types — however, were always there, but as the Orthodox Service of Supplication, the Akathist, says, “Then was the type, now is the fulfillment.” Christ himself has become the “sacred marker,” the ultimate measure of all the space in our lives, whether Church or home.

Sergius Bulgakov, the Russian theologian-philosopher, summarizes the point in his classic book, The Orthodox Church:

Even in the darkness of paganism, in the natural seeking of the soul for its god, there existed a ‘pagan sterile church’ . . . which attained the fullness of its existence only with the Incarnation. (p. 15)

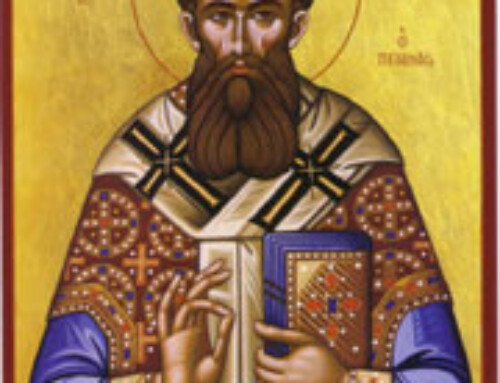

III. The Theology of the Icon

Because the faithful in the Orthodox East believe that Jesus Christ is the final hierophany which makes all space sacred, he takes from the Church this understanding and creates such a space in his home. He “sets aside” — and to “set aside” literally means “sacred” or “holy” — a physical place in his home. The sacred space in the home becomes the pre-eminent passage from one dimension to another, from here to there, from this life to God’s life. Maintaining that space, therefore, serves as a constant reminder that from morning until night one must seek God’s will, while still living in this fallen and profane world.

But what will occupy this sacred space in the home? In the Christian East, above all, it is the Icon. For the Orthodox Christian it is the theology of the Icon, which he is taught from his earliest days in the Church, that expresses the meeting place of “that world and this world,” the “sacred and profane.” The Western Christian may not at first understand this, thinking the icon to be mere religious “art.” But there is indeed a rich, but different, theology to Iconography, literally “image writing.” Fundamentally, the Icon, in maintaining a point of contact between these two dimensions, keeps a certain and necessary “tension” in the life of the faithful, lest he completely succumb to the secular pressure of this world, i.e., the bills, the clothing, the work, etc. The Icon can function in this way because it is never the relative product of an artist’s creative imagination. That it is never merely related to this world can be immediately recognized when one notes a certain “stiffness,” a slight awkwardness, a feeling of not being totally comfortable in the space of a world fallen from God. How different this is from a tender picture of a child, a portrait of one’s aunt, or even a magnificent marble statue of David the Prophet. And yet, even if not at first understood by the Western eye, it is precisely critical in the sacred space of the home because it functions as more than art!

And as it does so function, this Icon — often called a “window” which allows the flow between heaven and earth — will remind the faithful that a prayer life, undertaken while standing in the sacred space, keeps communion with God urgent. Thus he will pray there at regular times of the day according to his “rule of prayer,” but not only at those times of prayer. The Orthodox Christian can “sense” the presence of the Icon radiating from within the sacred space, even if he or she is in a far distant room of the home. And just as in the Church itself, the sacred space in the home will therefore again speak the truth: once in history God entered the space of this profane world and revealed, as the utter hierophany, “his only begotten Son” (John 3:18). He is the ultimate sacred marker which has finally fulfilled our yearning for sanctification and order.

Father Joseph is the pastor of St. Anthony Orthodox Church in Bergenfield, NJ, and the Director of Theological and Pastoral Education in the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese in Englewood, NJ.