ON CHANGE

by Fr. Anthony Hughs

Fr. Hughs is the rector of St. Mary Orthodox Church, Cambridge, Mass

I realize more and more clearly that Orthodoxy is the principle of absolute freedom.1

Fr. Alexander Elchaninov

Abraham Heschel’s writings, particularly on the state of modern religion, ring prophetic and true. In a few words he distills for us the crisis of contemporary religion. We would do well to listen to such voices.

The human side of religion, its credos, rituals, and instructions is a way rather than the goal. The goal is “to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God. When faith is completely replaced by creed, worsahip by discipline, love by habit; when the crisis of today is ignored because of the splendor of the past; when faith becomes an heirloom rather than a living fountain; when religion speaks only in the name of authority rather than with the voice of compassion, it message becomes meaningless.2

What message could be more apropos for the Orthodox Church? Here we are in the twentieth century in a position to offer so much to so many, but we haven’t yet decided what century it is! Can we possibly know who we are if we do not know where we are?

The past does not exist; the future always eludes us. All we have is the present. To live in the present demands engagement, and that always requires meaningful and significant change. Our model is the Incarnation itself. The Lord became human and yet his divine nature and person remained unchanged. In the same way the Church throughout the ages has incarnated truth in the specific garment of the time, culture, and place in languages, art, music, liturgical traditions, canons without dogmatizing them and without changing Her creed. Some Christian confessions have dispensed with classical doctrine in an effort to become relevant. We, on the other hand, have made irrelevance sacrosanct by dogmatizing everything. At the same time there are contemporary issues of grave importance to address that call for a purification of our perceptions and a radical commitment to the truth which alone can liberate and save humanity. Openness, courage, creativity, and compassion are called for.

Usually the invocation of orthodoxy happens with a boasting aboutfaithfulness to what is genuine and authentic. Boasting means a demand for common recognition of and reverence for what has been handed on, but also for those people who maintain and represent it. thus, orthodoxy comes to function as a means for justifying not somuch conservative ideas as conservative people — to serve often for the psychological veiling of cowardice or spiritual sterility. Those who will not risk or cannot create something new in life fasten themselves fanatically to some orthodoxy…protectors of the forms, interpreters of the letter. They transform finally, any orthodoxy into a ‘procrustean bed’ where they mutilate life in order to make it fit the demands of their dogma.3

Our misguided concept of the Church as rigidly unchanging hinders our response to the contemporary world. Note that Orthodoxy is still governed by a structure dependent on the existence of empires and emperors long dead and canons that have no practical

application. Note that while the rest of Western society struggles with issues that impinge upon real human life, we are lost in an attempt to resurrect ancient worlds, all the while saying nothing to those who desperately need cogent answers from us. Or, if not answers, then at least a compassionate, nonjudgmental ear.

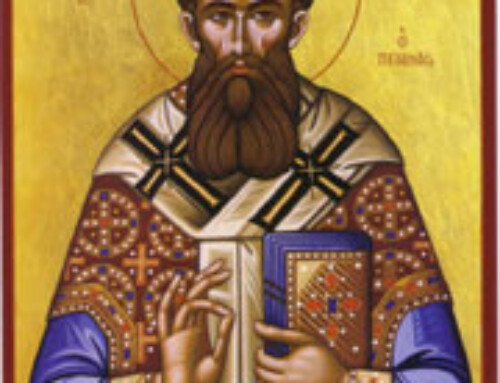

The Cappadocian fathers, with sheer genius, addressed their age in its own terms and produced an unsurpassed theology. That theology is so exquisite precisely because it reflects not only the age, but also the dynamism, methodology, and intent of the Gospel itself. It was not merely a parroting of what had already been said. The Cappadocians reformulated the message of the Church in new words for their new age. Their use of the language and concepts of Hellenism was bold, controversial, and risky. But who can now argue that it should not have been done? Our complicated age calls for that kind of response. Orthodox “political correctness” — speak these words, wear these clothes, avoid these issues (the cult of externals) — is at worst a betrayal of the Gospel and at best a tragic, momentary, but recurring temptation in the life of the our Church. The Body of Christ is anything but a purity cult for a select and arrogant few.

The time-honored tenant of the Church is that truth does not change. By “truth” we mean that which has been revealed by God about Himself and His relationship with creation. This is theology proper and includes those two fountains of all Christian dogma: the Holy Trinity and the Incarnation. This is immutable. On the other hand, vestments, music, iconography, canonical discipline, liturgical practice all has undergone significant change through the centuries. While all of them reflect the unchanging truth none of them exhaust it nor do they pass from age to age, culture to culture unaffected by the particulars of time and place. The Church of Christ cannot be locked into a specific era. She demonstrates in every age the immutable truth of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, that is, if She is being true to Her Lord. This means that the faithful Church is dynamic and alive, not static and lifeless. This means that the Church can –no must–respond to the issues of the time courageously, and this means change. Are we eternally bound to the tyrannical argument that because something has never been done it must never be considered? Is it not obvious that transparency, repentance, honesty, humility, compassion, courage, dialogue, and vulnerability are more effective tools than their unchristian counterparts defensiveness, arrogance, and triumphalism?

We must find a new voice to speak the unchanging Gospel to our new age. We must search for cogent answers for the burning issues of our time. It is time to seek out and institute meaningful changes that are at once faithful to what is truly ineffable and courageous enough to touch the lives of our contemporaries. The Church has been given the commandment to embrace everyone from the most disaffected to the most highly exalted just as Christ did when he stretched out His arms on the Cross. Everything in our present condition militating against this must be thoroughly examined and either transformed or discarded.

We cannot deny that the Church changes from age to age in those things that are accidental to the particulars of history and culture. Empires rise and fall, bishoprics disappear, others are formed all without altering the truth one jot or tittle. Clerical dress changes as do styles of hair like everything else that are not immutable. Such things are accidental. They reflect the engagement of the Church with the present and this is of preeminent importance. Without this kind of response the Church becomes marginalized, ineffective and, I daresay, unfaithful.

The Cappadocians did not fear to utilize the language of Hellenism to transmit the faith. Our contemporary world also has a “language.” Perhaps it is time to take their example and learn that “language” so that we can speak to the present. This, I believe, is the struggle for the soul of the Church in the twentieth century.

Notes

1. Alexander Elchaninov, Diary of a Russian Priest, (St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, New York, NY: 1982), p. 53.

2. Samuel H. Dresner, ed., I asked for Wonder: A Spiritual Anthology, Abraham Joshua Heschel, (Crossroad, New York, NY: 1997) pp. 39-40.

3. Christos Yannaras, Elements of Faith, (T&T Clark: Edinburgh, 1991) pp. 149-150.