Word Magazine March 2000 Page 6-7

KEEPING THE FAITH IN THE

HOLY DAYS

By Father Joseph Allen

The key to “keeping the Faith in the Holidays (holy days)” is in the understanding of “time.” In the Orthodox East, where we call such days “Feasts” or “Feastdays,” this especially means both the place of time in our lives and our use of time.

First, regarding the place of time, the religious anthropologists have shown us in many ways that the human being, from the beginning, understood that the feastdays and celebrations were an organic and essential component in his whole world-view, in his way of life. They discovered that the homo religiosus, the religious man, lived in the “rhythm of time” — where beginnings and endings, youth and aging, birth and death, were truly acknowledged as real. Thus the feastday was not something extraneous or accidental to his life; his observation of what was happening in the cosmic occurrences all around him kept this rhythm of time central. Neither was the feast a simple “break” from his usual life of hard work. Far more important to his very being, the feast was — as it should be for us today — a “marker” of such times of change and transformation. Indeed, each celebration was its own “rite of passage,” from this point to that point, from this time to that time. And the religious man lived within that cycle, quite naturally.

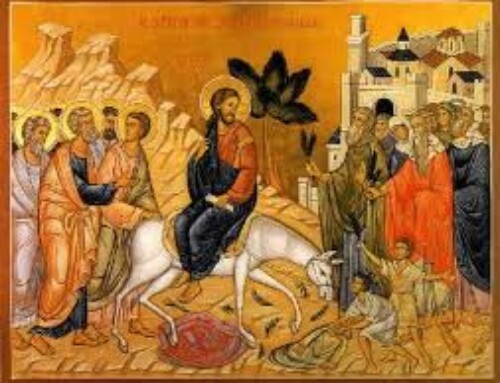

But when God comes into our world, the Orthodox believe that He takes that which is “natural” to all life, and entering it, infuses it with new meaning. Thus, for example, the early Christians understood that at Christmas, the Nativity of Christ (which was celebrated at a cosmic time of increasing “light” i.e., as a shift to longer days occurred), a radical change occurred in which God Himself now fully enters our natural time and transforms it forever. (Or to use the words of St. Gregory the Theologian: “The Creator bows down to his own creation.”) The same with Epiphany, which in the Orthodox East is also known as Theophany: God “reveals” Himself in the form of the Trinity, and the entire cosmos — now symbolized in the primordial substance of life, water — is infused with God’s presence. At Easter, or Pascha (“passover”), the final transformation, the final “rite of passage,” is realized as we are taken from death to life. And so on.

In each case where such a holy day is celebrated, because God enters it — reveals Himself in it — natural time, which is still important to us, is now celebrated as something that He has transformed, as something new: “Behold I make all things new!”

And so the question: how indeed can we keep our Faith in the feastday, the holy day, without this understanding of time? Do we moderns arrogantly think we are beyond the natural “rhythm of time?” And have we forgotten that a holy day is something which God makes holy when He transforms this natural time into new time? In short, have we lost something that earlier believers held as “critical” to their lives? something they could almost intuit as central to their living?

If one can answer “yes” to any of these questions, we must then ask: What are we to do in order to reestablish the proper place of our Faith in the holy days? The first thing to do is truly to return to this root understanding of “time!” And here we enter our second dimension: our use of time.

The Orthodox Christian continually re-establishes that meaning by placing time with the rhythm of “Fast and Feast.” Before each feast there is a fast, a time which includes abstinence, prayer and almsgiving. What is the meaning of this Fast, this season of fasting?

Never have there been so many misunderstandings and abuses regarding the meaning of fasting, as “new spiritualities,” religious cults based on pop psychology, etc., abound. And yet, if we do not understand the true meaning, we cannot be led to a proper perspective of time leading up to the feast day — and therefore to our task of keeping our Faith in that holy day.

Basically, the purpose of a fast — and a fasting season — is to gain mastery over oneself. It is seeking to liberate oneself from those elements in our world which precisely seek to hold us in bondage: greed, revenge, gluttony, hate, gossip, etc. It is never only about “food,” as if God is pleased when we do not eat. It is never separated from prayer. It is also never about afflicting oneself with suffering and pain. Indeed, in the services of the Orthodox Church, we are reminded that “the devil also never eats!” And when we fast, the Gospel reminds us that we are “to anoint our head and wash our face, that our fast will not be seen by men, but by our Father who sees in secret” (Matthew 6:16-18). Food, of course, has always held its important place in the season of the fast because it is a first-line passion, a temptation, as everyone already knows, which truly does hold us “in bondage.” It takes us immediately to the point simply because we need food to live in this earthly life. Thus, abstinence relative to food is a veritable symbol of the more global task of liberation from dependence on this world, and its ways: eat, eat, eat; violence, violence, violence; consume, consume, consume, etc.!

These — and others like them —militate against our seeking a dimension of life beyond this earthly world. Indeed, we must seek to be free for something, but first we must struggle to be free from something: the earthly passions which seek to possess us.

And that’s the point! We fast not only as an end in itself, but as a means to an end: to enter fully and organically into a holy time with God, and for our present purposes, this means the use of time culminating at the holy day, the sacred feastday.

Therefore, this season of the fast — which leads to the feast — is never a time of “business as usual.” It is indeed a special time, one in which a struggle leads to a goal. It must, however, remain humble and never lead to judgmentalism or arrogance. In the seventh century, St. Dorotheos well-noted this truth: “When one fasts, thinking he is achieving something especially virtuous, he fasts foolishly, for he soon begins to criticize others and to consider himself something greater.” Or to use the words of the Great Apostle Paul in his Epistle to the Romans: “Let him who eats not despise him who abstains, and let him who abstains not judge him who eats for God has welcomed him. Who are you to judge the servant of another?” We see in this way that a fast, and a season of the fast, is never limited to the excesses which may come into our minds and mouths, but which also proceed out of our minds and mouths!

Another critical element which truly belongs to the season preparatory to the holy day is almsgiving. When almsgiving is combined with prayer and fasting, those in the Eastern Christian Tradition believe they are creating the best environment for keeping our Faith in the celebration of a Feastday.

Again, like prayer and fasting, “when you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your alms may be in secret, and your Father, who sees in secret, will reward you” (Matthew 6:1-4). Such is the humility needed when almsgiving is practiced. St. John Chrysostom, a great fourth century presbyter and Bishop of the Church, says we simply cannot be saved without giving alms. He reminds us that the wealthy can come closer to God only to the degree that they are charitable. Like Chrysostom, St. Basil the Great is even more specific: A person who has two coats and two pairs of shoes while his neighbor has none, is a “thief.” We must wonder, of course, what this says about the excesses of commercialism which abound during this very same season of preparation for the holy days!

And yet, almsgiving during the preparatory time of the fast is merely reflecting God’s love: “If any one has all the world’s goods, and sees his brother in need, yet closes his heart against that brother, how does God’s love abide in him?” (I John 3:17) Just as in a person’s stewardship for his or her parish, his or her community of Faith, if such giving is to be of any value, it must be a spiritual “offering of sacrifice.” One cannot merely give what is “left over” after all his own needs are satisfied; one must take from the essentials of his own life and offer it. Is this not the meaning of the poor widow in Luke’s Gospel?

Many rich people put in large sums. And a poor widow came, and put in two copper coins, which make a penny. And Jesus called his disciples and said to them, “Truly I say to you, this poor widow has put in more than all the rest: for they contributed out of their abundance, but she out of her poverty has put in of her essential living.”

And so, in attempting “to keep our Faith in the holidays (holy days),” understanding both the place of time and our use of time, is essential. Within the “rhythm of time,” natural to all of life, we cannot be passive. We must ourselves “struggle” during the preparatory time of fasting in order to truly arrive at a celebration of our Faith during the Feast Day. Remembering that any holy day is a day when God makes Himself known to us, a day when the doors are thrown open, allowing us to draw near to His presence —that is, precisely to enter into His Kingdom — the struggle on our part to get there is critical. For as Our Lord Himself said: “The Kingdom of God is taken by force.”

Father Joseph, pastor of St. Anthony Orthodox Church in Bergenfield, is the Director of Theological and Pastoral Education in the Archdiocese, and North American Chaplain of the Order of St. Ignatius of Antioch, located in Englewood, NJ.